United States Economic Forecast 1st Quarter 2020

22 minute read

27 March 2020

The coronavirus outbreak is driving changes to the US economy so quickly as to make forecasting even more challenging than usual. But we can pin down both short- and long-term ways in which this shock is affecting the economy.

Introduction: The economic consequences of COVID-19

“External shock” is a technical-sounding term that economists use to describe a random event that disturbs the economy. Wars are external shocks; so are earthquakes … and diseases. COVID-19 is an external shock that has the potential to upend the trajectory of the economy. How things turn out depends largely on the response of economic policymakers and public health authorities—and the nature of that response is changing hourly.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

Before the outbreak of the novel coronavirus, the US economy looked to be doing moderately well—our baseline was for growth, albeit fairly slow growth. There were some weaknesses: Manufacturing had been in a funk for about a year, international trade had stopped growing, and business investment was falling. But the glide path to a soft landing was in sight.

Then came the novel coronavirus SARS-COV-2, and its associated disease COVID-19. The initial impact on the US economy—just after it showed up in China—appeared to be muted: Supply chain impacts would affect some companies, for sure, but the overall impact on the United States was unlikely to be large.1 That forecast crumbled as the disease spread out of Asia, and the number of cases started to climb. From February to March—within one month—the average 2020 real GDP forecast from a Wall Street Journal panel of forecasters fell from 1.8 percent to 1.3 percent.2

The shock is affecting the US economy in four ways.

First, the global economy is already experiencing a sudden, significant downturn. The initial supply chain problems from China will likely be multiplied as other countries experience outbreaks of the disease. US producers have not yet felt the full impact of the China shutdown, but the next few months may see significant interruptions of activity related to breaks in the global supply chain.

Second, the global decline in commodity prices—particularly oil prices—will likely reduce investment spending in the United States. Mining—mainly oil and gas extraction—accounted for 5 percent of private investment spending in 2018 (the last year available). The oil price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia will probably drive investment in this sector down substantially, reducing demand for manufactured goods such as pipes and machinery. In 2015–16, a similar decline in oil prices drove the entire manufacturing sector into decline. The impact now on an already weak US manufacturing sector is likely to be significant.

Third, even under relatively benign assumptions about the future course of the illness, US GDP growth will likely plunge in the first quarter, and very likely fall further in the second quarter. The somewhat spontaneous adoption of social-distancing measures that picked up in the second week of March may reduce the speed of the spread of the disease—and will very likely be reflected in reduced economic activity. The steep decline we are already seeing in sectors such as travel, leisure, and hospitality—and the decline in durable goods purchases and factory production—will push demand and GDP into a tailspin. Reports of mass layoffs suggest that unemployment numbers will jump as well.

Fourth, financial markets have experienced a crash. There is no more appropriate word for it. The headline-grabbing equity market decline is itself probably not a huge problem. In 2000–01, financial markets continued to function well even as equity markets declined substantially. The larger problem now is in corporate debt markets, particularly those that issued riskier debt. The current recovery has seen an unusually high share of lower-rated corporate debt.3 A larger than usual share of companies are likely to feel the squeeze of fixed interest payments as revenues fall, and defaults will likely rise. Credit spreads—the difference between the yield on highly rated corporate debt and low-rated corporate debt—spiked in March. That could create knock-on effects as financial market institutions start to be concerned about their counterparties in short-term credit markets. The Fed has been willing—and has taken extraordinary steps—to provide as much liquidity as the market needs, but even under the best of circumstances, credit will be harder to get, and the cost of capital higher.

We believe that the immediate economic impact is likely to fade within the year, as a vaccine or the natural progression of an epidemic reduces the number of infections and consumers venture out of their homes to resume eating at restaurants and shopping for more than groceries and hand sanitizer. The economy will likely recover quickly once that happens. And over the five-year horizon of our forecast, longer-term questions will remain key to understanding how the economy will develop. We continue to pay careful attention to these in our forecast, and we discuss them in our sectoral descriptions.

Scenarios

Our scenarios are designed to demonstrate the different paths we might expect the US economy to follow in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. In the first two scenarios, we assume that the disease outbreak begins to recede by the beginning of May, and people are able to return to normal activities during the late spring and summer. In the third scenario, outbreaks of the disease continue to affect economic activity for over a year.

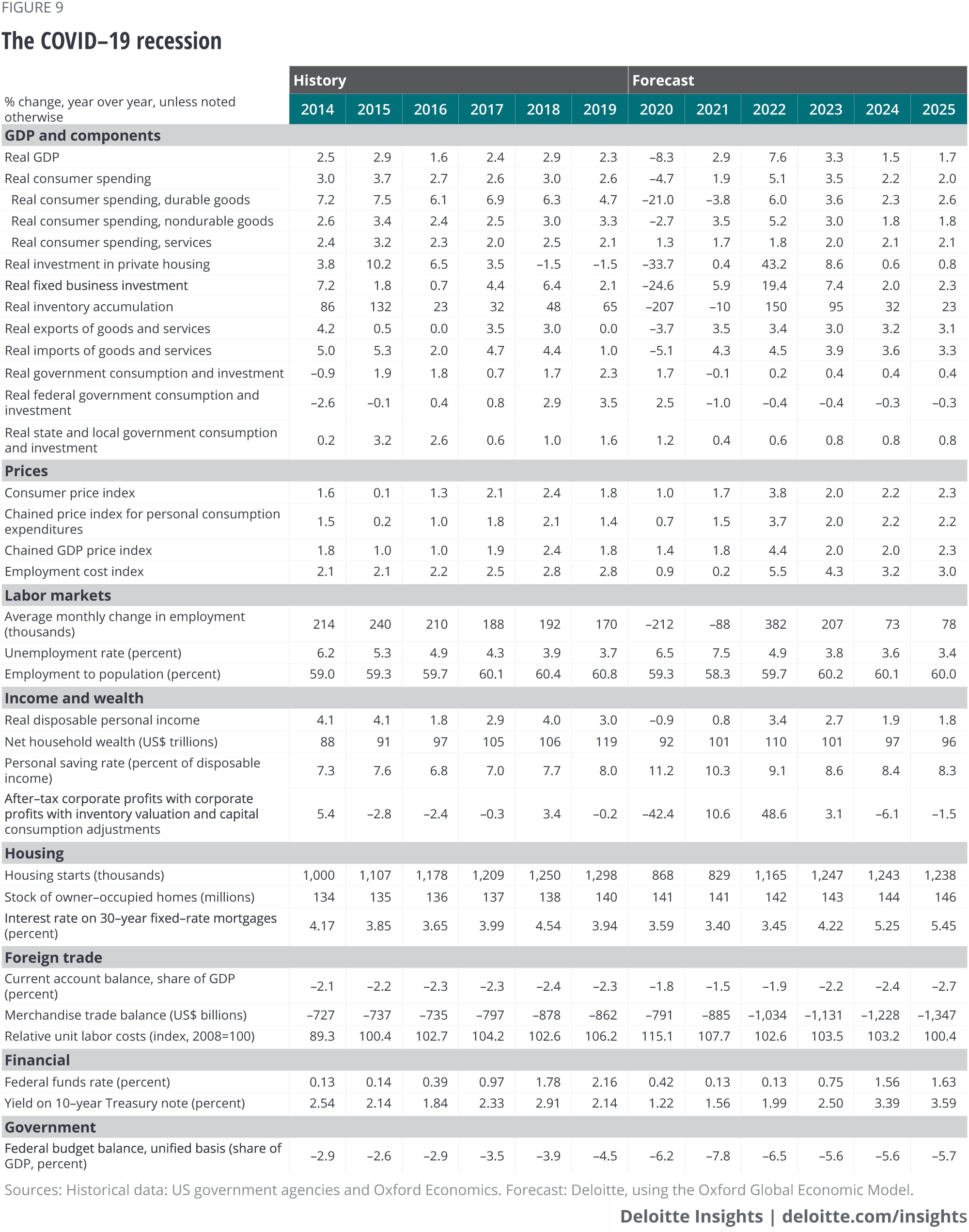

The COVID-19 recession (50 percent probability): The immediate impact of COVID-19 is a huge drop in economic growth. GDP falls by more than twice the amount of the average postwar recession but begins to recover in late 2020 as the disease is brought under control. Aggressive monetary and fiscal policy help jump-start the recovery, as does recovery abroad. GDP falls 8.3 percent in 2020 but starts recovering in 2021.

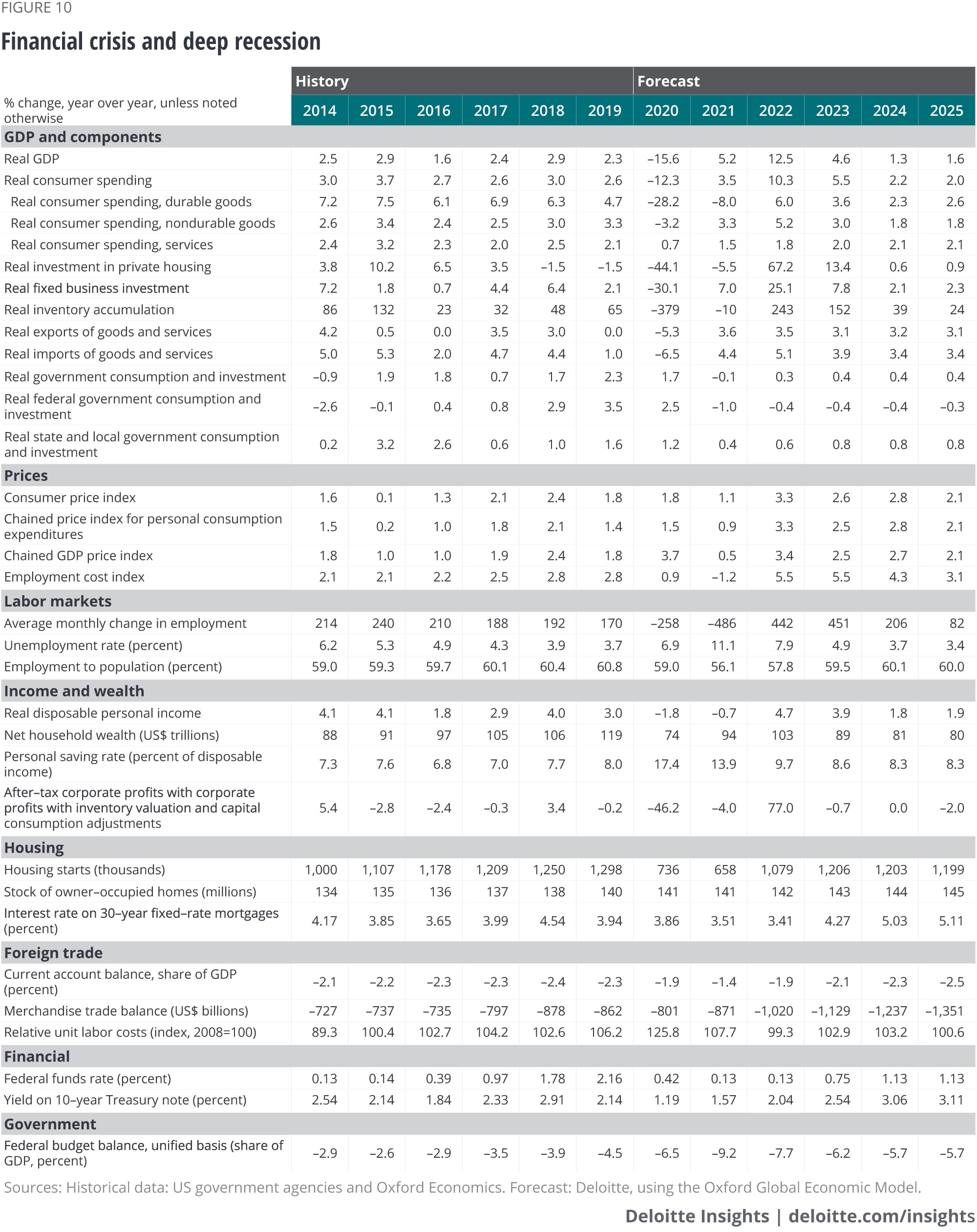

Financial crisis and deep recession (30 percent probability): Economic activity plunges as the COVID-19 outbreak affects both the economy’s supply side and demand side. The shrinking economy uncovers weak financial structure in some economies and sectors, particularly those that have a substantial debt burden. This stresses the financial system and adds to the problems of companies that are more robust financially, as lending dries up. The combination of supply-side limits, weak demand, and financial crisis throws the economy into a recession. Quick, substantial fiscal and monetary intervention creates enough demand to lift the economy out of recession by mid-2021, and 2022 sees a strong recovery.

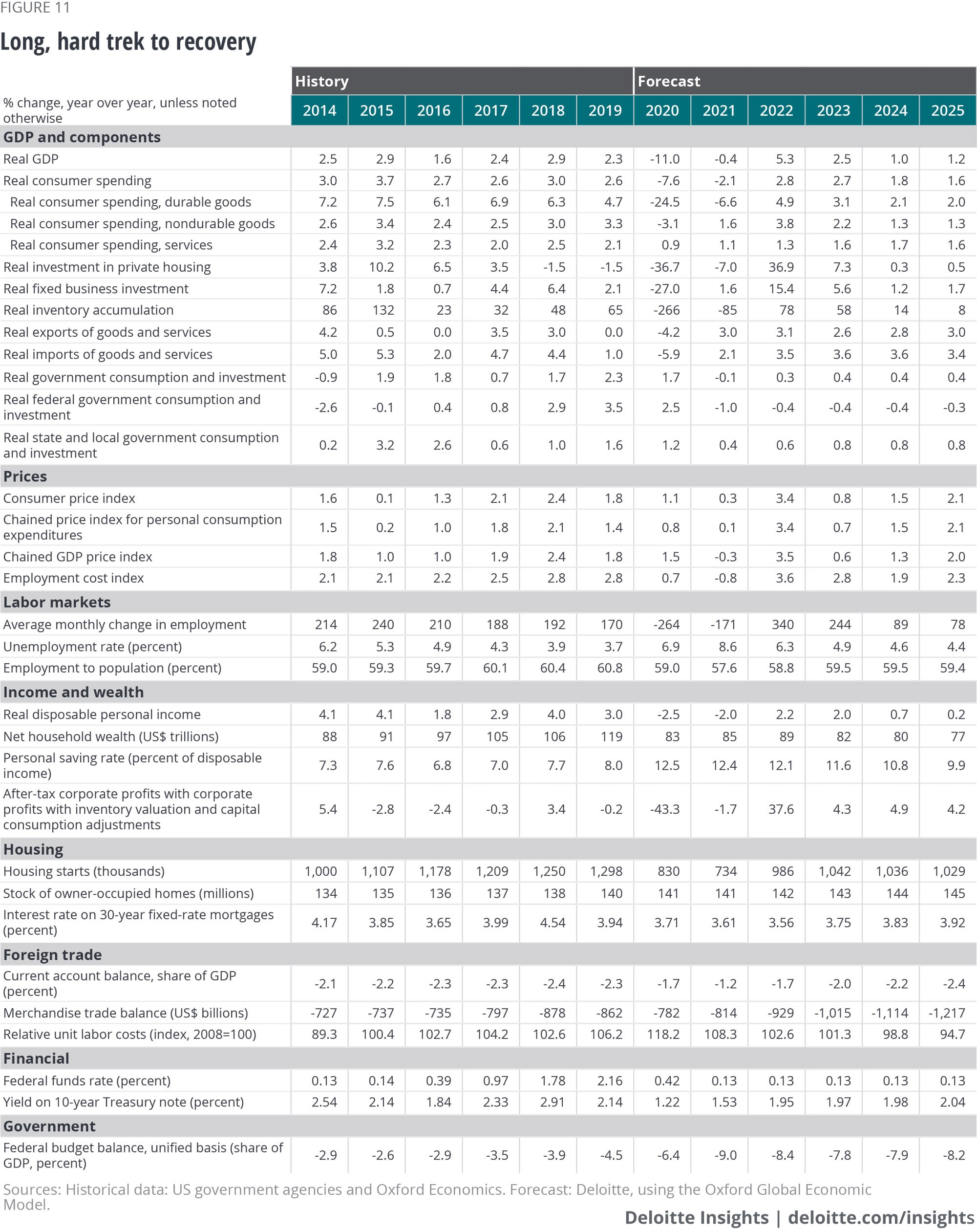

Long hard trek to recovery (20 percent probability): As the economy struggles to recovery from the initial recession, regional outbreaks of COVID-19 continue for about two years, or a bit longer than the 1918–19 outbreak of Spanish influenza. Each regional outbreak is accompanied by interruptions of economic activity in that region. This is compounded by overall slow growth, as consumers put on hold big-ticket purchases such as automobiles and home renovations. As the disease’s impact dissipates, the US economy struggles to recover. Households and businesses are wary at first of making major expenditures. As a result, growth remains slow for another year, until people are confident that the disease is not going to recur. After falling substantially in 2020, GDP is flat in 2021, and unemployment remains high. Growth then picks up to 3 percent or more by 2023 and remains high for another year because of pent-up demand for big-ticket items, combined with very accommodative monetary and fiscal policy.

Sectors

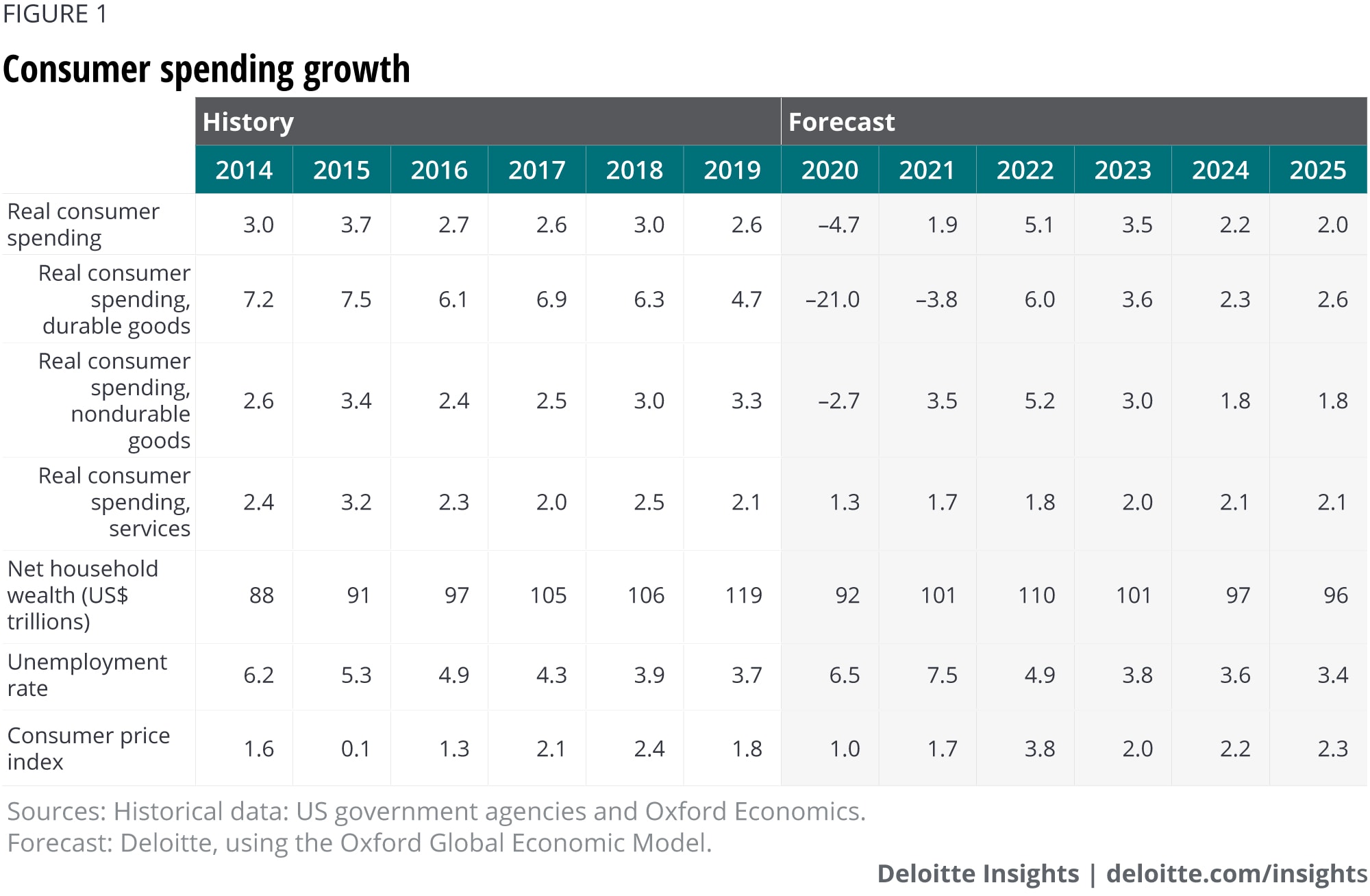

Consumer spending

For all the daily speculation about how political developments might affect consumer choices, when it comes to spending decisions, political noise seems to be just that—in the background—to consumers who seem focused on their own situations. COVID-19 disease is different: Anybody who has encountered an empty shelf in the grocery store can attest to an immediate impact. But the short-term lift to retail sales—especially online sales—will almost certainly be offset quickly by the lack of traffic in car dealerships, furniture showrooms, and other places where people buy big-ticket items. And consumer confidence will almost certainly take a hit.

Beyond the next few months, the key question is jobs. As long as employment growth picks up as the outbreak wanes, consumer spending will pick up as well. If employment lags even after the disease runs its course, consumers will be reluctant to return to purchase those big-ticket items.

The medium term presents a different picture. Many American consumers spent the 1990s and ’00s trying to maintain spending even as incomes stagnated. But now they are wiser (and older, which is another challenge, as many baby boomers face imminent retirement with inadequate savings).4 The steep decline in the stock market underlines the problem: Anxiety about 401(k) balances may constrain spending and require higher savings in the future. And although American households seem to face fewer obstacles in their pursuit of the good life than just a few years ago, rising income inequality could pose a significant challenge for the sector’s long-run health. For instance, low unemployment hasn’t alleviated many people’s economic insecurity: Four in 10 adults would not be able to cover an unexpected US$400 expense only by borrowing money or selling something.5 (For more about inequality, see Income inequality in the United States).6 That’s not just a source of long-term concern—it may become an important problem as the country responds to the COVID-19 outbreak.

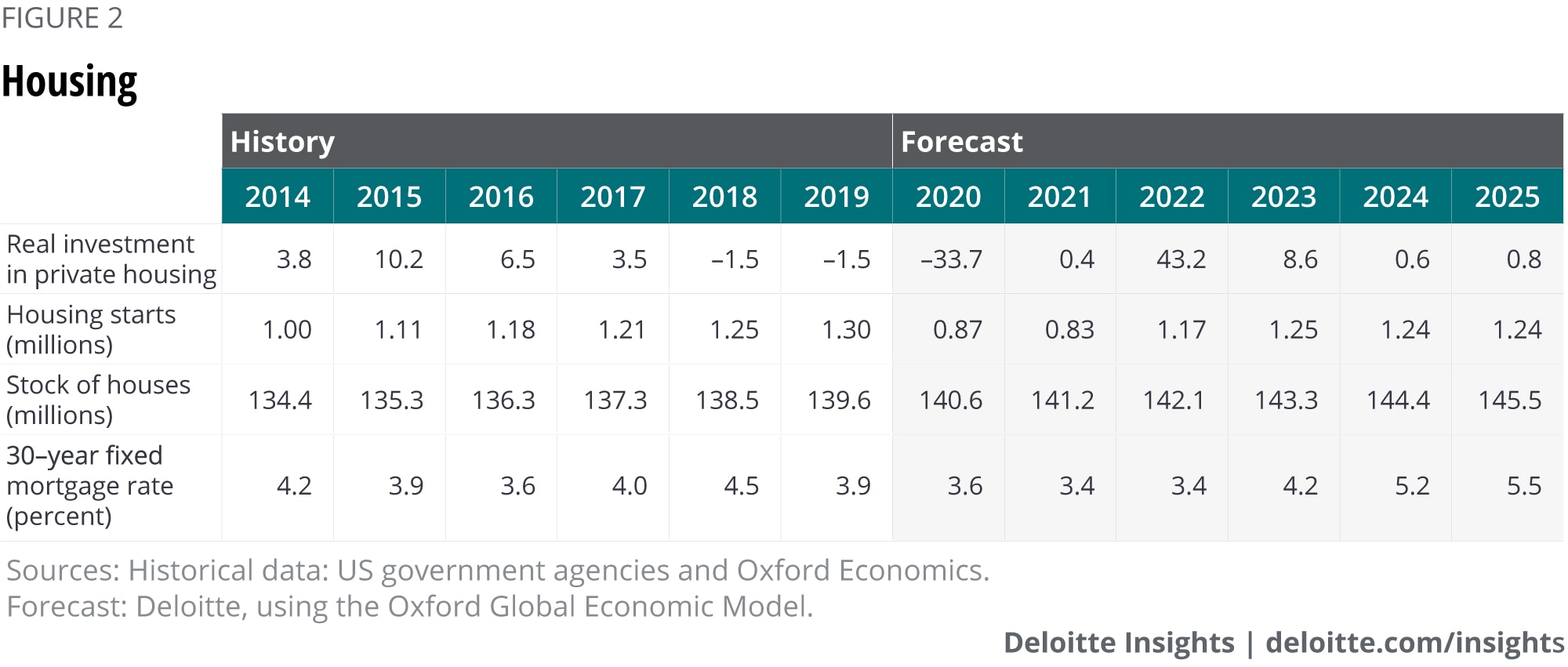

Housing

The housing market was picking up some steam before the outbreak hit. Housing construction appeared on an upward trajectory in the last few months of 2019 and in early 2020, prompting us to be a bit more optimistic about housing in the short run. Construction activity may be a bit soft in the next few months because of supply chain and labor shortages. But the immediate fundamentals still look positive, and social distancing may have a smaller impact on the construction sector than on some others.

However, we remain a bit more pessimistic in the medium term. We created a simple model of the market based on demographics and reasonable assumptions about the depreciation of the housing stock,7 and it suggests that housing starts are likely to settle into the 1.1–1.2 million range. In the baseline forecast, the housing sector stagnates as the economy weakens in the next year or two and then stabilizes for the forecast’s remaining years.

Housing remains a smaller share of the economy than it was before the Great Recession, and that’s to be expected. In some ways, it has been a relief to see the sector return to “normalcy.” But with slowing population growth, housing is highly unlikely to be a major generator of growth for the US economy in the medium and long run.

Some folks reacted to last year’s slowing housing market with alarm, remembering something about how the last recession was connected to a housing problem.8 It’s certainly not a happy sight, especially for anybody in the home construction business. But a construction decline didn’t cause the last recession: Construction began subtracting from GDP growth in the fourth quarter of 2005, two years before the recession, and GDP growth remained healthy. It was housing finance that ultimately created the crisis, not housing itself. Today, housing accounts for just under 4.0 percent of GDP, down from about 6.0 percent in 2005. The sector simply isn’t large enough to cause a recession—unless, once again, huge hidden bets on housing prices come to light.

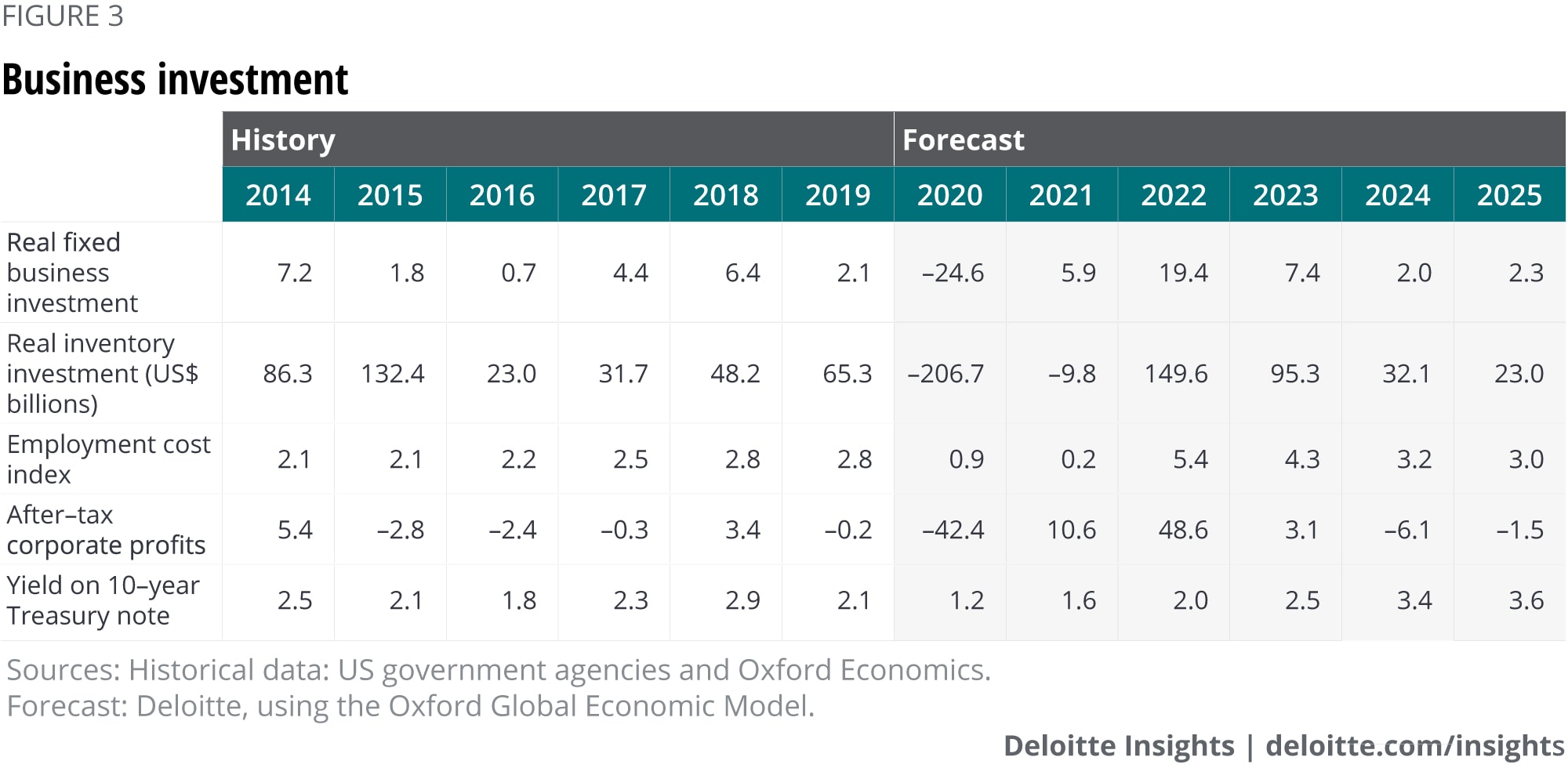

Business investment

Policy uncertainty has been one of the biggest potential roadblocks to strong investment spending. Businesses were still reckoning with the investment implications of the 2017 tax bill when the US government introduced additional uncertainty with a significant shift in international trade policy.9 Nor did the tax bill leave tax policy settled. And the November elections will provide plenty of opportunity for nervous business leaders to wonder about the long-term viability of new investments. On top of everything else, the Fed executed a 180-degree turn in policy in 2019, leaving Fed watchers arguing about what might happen next. Many officials cited trade tensions as one of the factors causing Open Market Committee members to change their recommendations about monetary policy.10

COVID-19 adds another source of uncertainty. Financing investment may become difficult very quickly, and future growth and demand are hardly assured. In the short term, businesses are more likely than before to put expansion plans on hold for the next few months.

Stepping back, business investment remains a problem area for more fundamental reasons. The cost of capital has been at historic lows over the past decade, but many business leaders have remained reluctant to take advantage of that cheap capital to raise investment. Economists, happy to find yet another research topic, have dubbed this the “investment puzzle.”11 Nothing that has happened in the past few years seems to have substantially altered that problem, and many analysts are skeptical that further rate cuts would spur new investment.

The imposition of tariffs on a wide variety of goods—and foreign retaliation in the form of tariffs on American products—creates even more uncertainty, particularly for manufacturing firms. Some CEOs face a painful medium-term dilemma: deciding whether their businesses need to rebuild their supply chains. Industries such as automobile production have developed intricate networks across North America and are reaching into Asia and Europe, based on the long-standing assumption that materials and parts can be moved across borders with little cost or disruption. Leaders can no longer take that assumption for granted.

That’s the bad news. But there’s good news. The Deloitte economics team remains optimistic about investment in the medium term, since the United States remains a fundamentally good place to do business. Beyond the impact of COVID-19, beyond the questions of tariffs and taxes, in the long run carefully considered investments will continue to provide businesses with a high payoff.

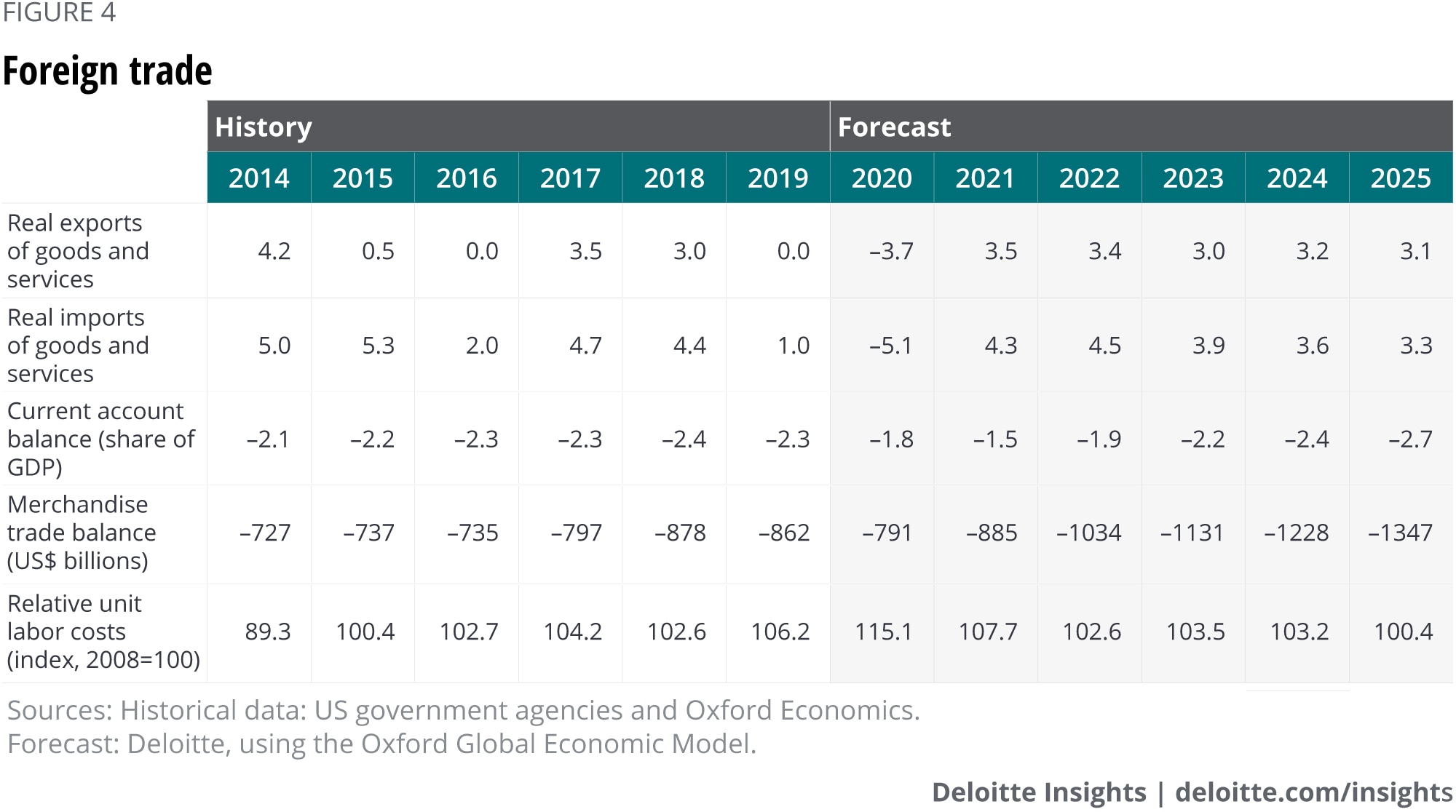

Foreign trade

Over the past few decades, business—especially manufacturing—has taken advantage of generally open borders and cheap transportation to cut costs and improve global efficiency. The result is a complex matrix of production that makes the traditional measures of imports and exports somewhat misleading. For example, in 2017, 37 percent of Mexico’s exports to the United States consisted of intermediate inputs purchased from … the United States.12

Recent events appear to be placing this global manufacturing system at risk. The United Kingdom’s increasingly tenuous post-Brexit position in the European manufacturing ecosystem,13 along with ongoing negotiations to replace the North American Free Trade Agreement, may slow the growth of this system or even cause it to unwind. The COVID-19 outbreak puts further questions on global supply chains that are not diversified. The problem for business is not just the short-term puzzle of managing until Chinese (and other countries’) production comes back on line. The more fundamental problem is that businesses are likely to realize that they need more robust supply chains—which means finding alternative suppliers in other countries.

But still, the biggest challenge now facing the global trading system is the unpredictable tit-for-tat explosion of trade restrictions between China and the United States. The agreement on the Phase-one deal did not significantly reduce uncertainty, since the deal made unrealistic assumptions about Chinese purchases of US goods.14

A key source of uncertainty lies in the fact that the president’s advisers appear divided about the ultimate goal of the tariffs and the trade negotiations. White House trade adviser Peter Navarro argues that the tariffs are necessary to reduce the US trade deficit and to help the United States strengthen domestic industries such as steel production for strategic reasons.15 This suggests that tariffs in “strategic” industries could be permanent. But Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross has stated that the goal is to force US trading partners to lower their own barriers to American exports.16 That suggests that the administration intends the tariffs to be a temporary measure to be traded for better access to foreign markets. So are trade restrictions meant to be temporary, or permanent? Nobody knows for sure.

A significant permanent change in border-crossing costs coupled with the desire for alternative suppliers could potentially reduce the value of capital investment put in place to take advantage of the pre-2016 global cost structure. Essentially, the global capital stock could depreciate more quickly than our normal measures would suggest. In practical terms, some US plants and equipment could go idle without the ability to access foreign intermediate products at previously planned prices.

With this loss of productive capacity would come the need to replace it with plants and equipment that would be profitable at the higher border cost. We might expect gross investment to increase once the outline of a new global trading system becomes apparent. But until businesses can be sure that the new investment will be profitable in the long run, they are unlikely to take the steps necessary to replace foreign products with US-produced goods.

In the longer term, a more protectionist environment is likely to raise costs. That’s a simple conclusion to be drawn from the fact that globalization was largely driven by businesses trying to cut costs. How those extra costs are distributed depends a great deal on economic policy—for example, central banks can attempt to fight the impact of lower globalization on prices (with a resulting period of high unemployment) or to accommodate it (allowing inflation to pick up).

Whatever happens, the tariffs are unlikely to have a direct impact on the US current account, except perhaps in the very short run. The trade balance is determined by global financial flows, not trade costs.17 Any potential reduction in the current account deficit is likely to be largely offset by a reduction in American competitiveness through higher costs in the United States, lower costs abroad, and a higher dollar. All three scenarios of our forecast assume that the direct impact of trade policy on the current account deficit is small. In the medium term, the fundamentals for global investment have not changed, and the United States is likely to run a substantial trade deficit reflecting the long-run demand for dollar assets.

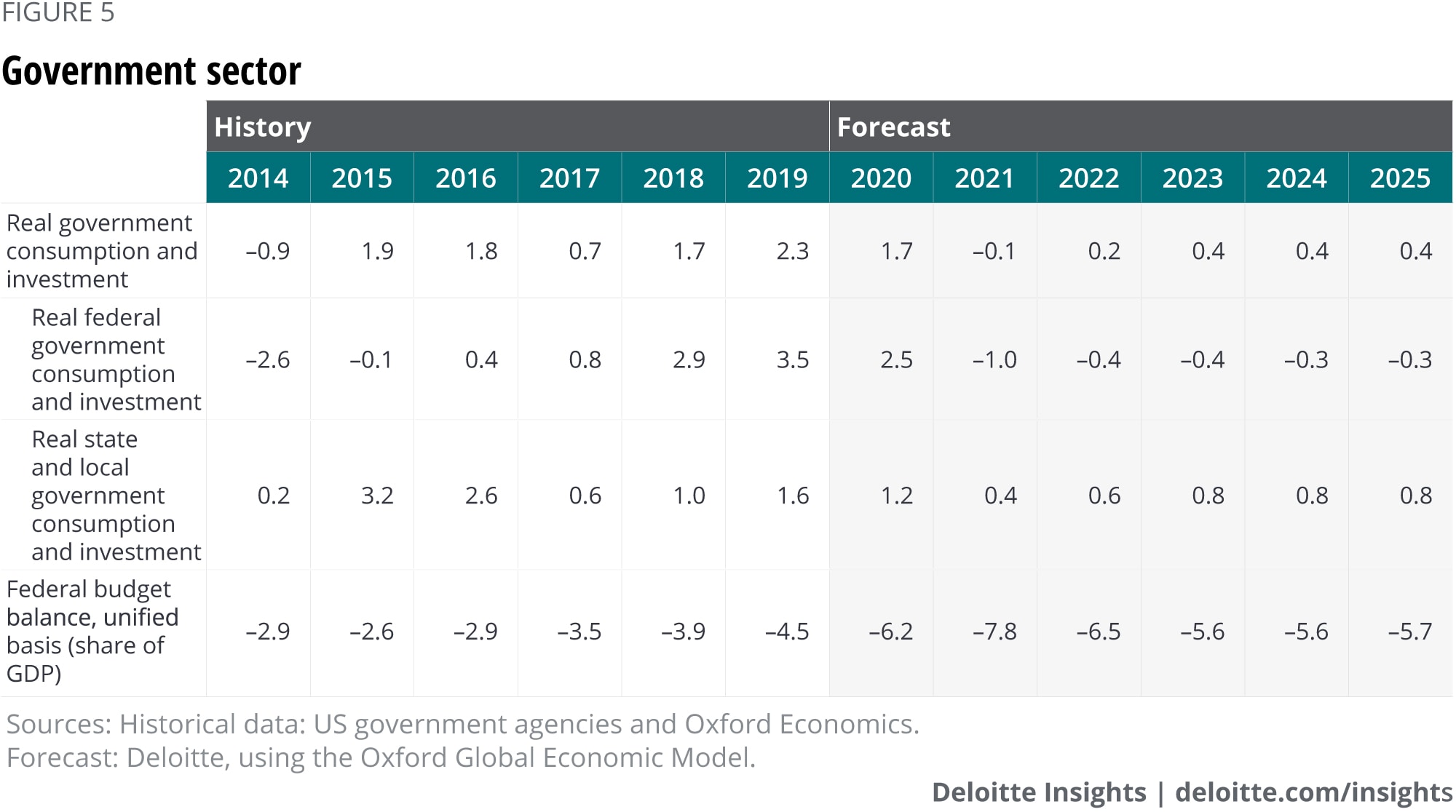

Government

Fiscal policy in the past few years has had two themes: lower taxes and higher spending. That’s an unambiguous recipe for larger federal deficits, and that’s what’s happened. FY2019 saw the deficit jump to 4.6 percent of GDP, a very high level when the economy is at or near full employment. Some of the deficit is because of higher federal outlays, which are around half a percentage point of GDP above the long-run historical average. But a larger share is because federal revenues are a full percentage point below the long-run average.

The COVID-19 outbreak is about to add substantially to the federal deficit. So far, the spending effort has proceeded in three stages.

First, in early March, Congress passed and the president signed a bill providing federal agencies with US$8.3 billion for fighting the disease. According to the CBO’s estimates, about US$1 billion will be spent this fiscal year, and about US$4.2 billion next fiscal year.

Second, in mid-March the US House of Representatives passed a bill to temporarily extend family and sick leave to many—although hardly all—workers who currently lack it. The program takes the form of a requirement for many companies (especially small businesses) to provide leave but pays for it through a refundable tax credit to those companies. (“Refundable” means that if the credit is greater than the company’s taxes, the government will pay the company the difference.)18 The Joint Committee on Taxation, Congress’s scorekeeper for tax policy, estimates that this will lower corporate taxes by almost US$90 billion in FY2020 and US$15 billion in 2021 before the program ends.

Third, the administration has responded to concerns about the overall economic impact of the disease outbreak by proposing a large spending program. The White House and Congress are still debating the exact form of the spending program—actually, three programs so far. With bipartisan backing for a massive outlay including checks mailed directly to people, it seems likely that a large stimulus will pass (and we have included this in our forecast). The exact form remains uncertain—for instance, the size of the check and whether the mailing is means-tested—but Congress will likely end up adopting a plan that aims to have immediate effects. This means that infrastructure spending, for example, is unlikely to be part of the plan.

There is little political appetite in the United States for budget discipline, so over our forecast’s five-year horizon, the deficit increases as a share of GDP to about 5.6 percent (in 2024) from 4.5 percent in 2019. That’s probably sustainable during this period: Global demand for Treasury securities remains very strong, strong enough to keep US interest rates low. Over the longer term, it is not, and US policymakers will eventually face some unpleasant, long-postponed choices (including decisions to be made regarding Social Security and Medicare). The sooner they make those choices—which will be painful to businesses as well as households—the more likely the country is to move back to a long-term sustainable budget path.

State and local spending has been growing over the past few years, and dealing with the COVID-19 outbreak will necessitate a bump in expenditures. The federal government will cover some of that, but some will require local governments to consider tax increases and/or spending cuts, especially since reduced business activity and rising unemployment will lower tax receipts. However, the ability of states and local governments to drastically cut spending is limited. About one-third of state and local spending goes to education, and under all possible demographic projections the overall number of students will continue to grow. Plus, after the surprisingly popular teacher strikes in 2018, states will look to avoid cutting education spending as long as possible. Some state and local governments also face mild to severe pension funding issues19 that will weigh on budgets.

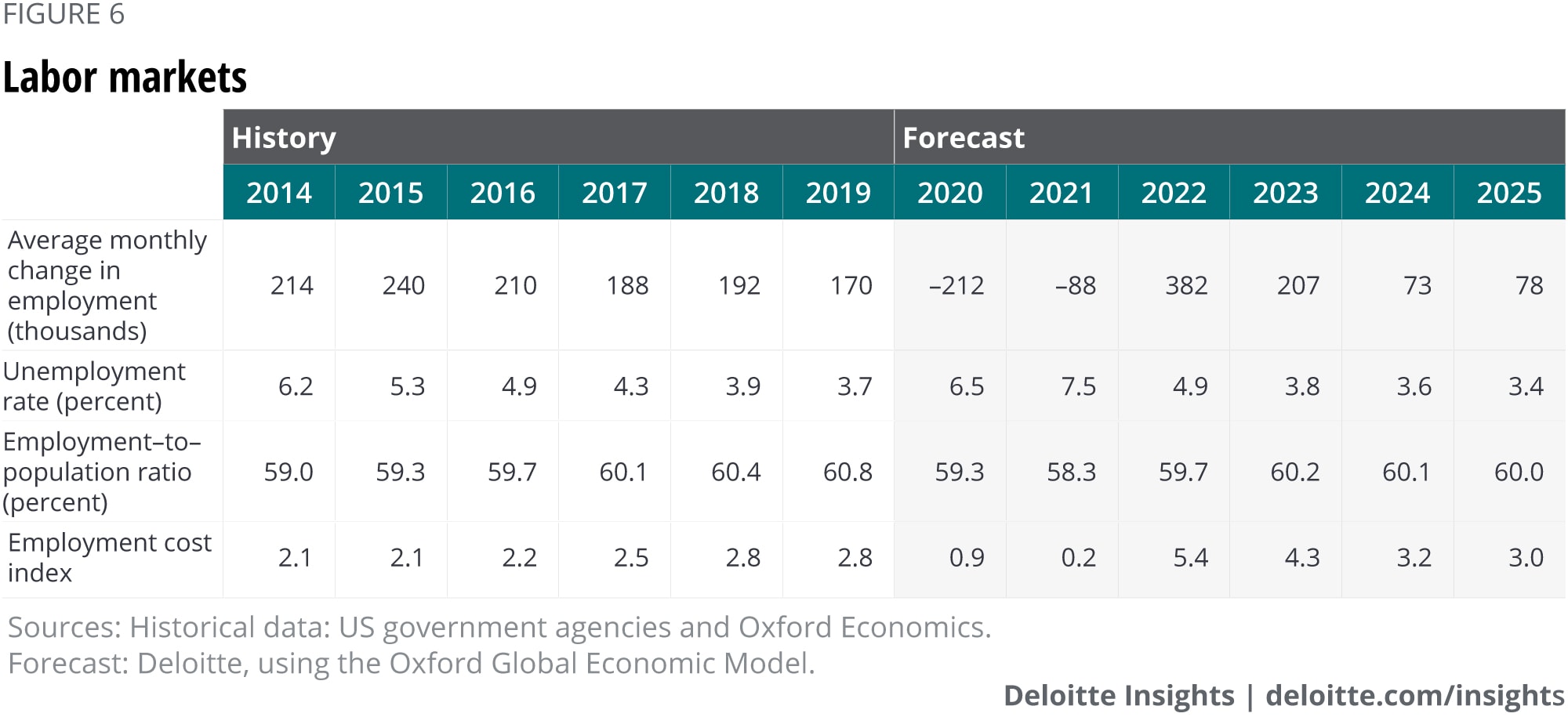

Labor markets

As the United States moves into social-distancing mode in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, workers will find themselves on one side or another of a key divide: whether they can do their work remotely or at home, or whether they need to be in a central location or in close contact with other people. Those who need to work in close proximity are clearly at higher risk of losing work time and pay. In addition, school closures will likely force some people to temporarily leave the labor force to care for their children. While these are strictly temporary issues, they may well affect labor-market data for several quarters.

The real question, however, is how the labor market performs during the outbreak—and as it abates. Coming at a time when many businesses believe they are experiencing a labor shortage, it would not be surprising to see “labor hoarding.” That happens when businesses keep workers on the payroll even when there isn’t work, because that’s cheaper than finding them again once demand picks up. Given the outbreak’s relatively short-term impact, labor hoarding is quite likely.

But small businesses that are entirely shut down, such as restaurants and bars, can’t hoard labor, and the week of March 16 saw a sudden uptick in unemployment insurance applications. In some states, the demand was so large that the application systems crashed.20 There is likely to be a very sharp decline in employment. It probably won’t be evident in the March number to be released on April 3, but the April number (released on May 8) could show a startling drop in employment. The forecast assumes a decline of 8.5 million by the end of 2020.

But the larger question is whether those businesses that don’t or can’t hoard labor will come back quickly once the outbreak comes under control. If that doesn’t happen, slow job growth might become a drag on the economy. The baseline forecast assumes that is not the case: Those 8.5 million people who lost jobs in 2020 are assumed to be rehired at relatively fast rates so that employment moves back to its long-run level by the end of 2022.

Over our forecast’s five-year horizon, however, fundamentals reassert themselves. Specifically, the aging of the population suggests that labor force growth will slow. On the other hand, there is still some room for workers who left the labor force after the financial crisis to return—and older people are more likely to work now than in the past.

One of the great questions of the recovery has been whether workers who left the labor force when the unemployment rate spiked could be enticed to return to work. Some particularly pessimistic analysts believed that many of those who left the labor force would not return.21 That, fortunately, turned out to be wrong. The “prime age” (25–54 years old) participation rate rose to 82.5 percent in 2019. That’s still a bit lower than the 83.1 percent reached in 2008 or the 84.1 percent rate in 1997–99. But it demonstrates that people will move off the sidelines and into employment if they have the opportunity.

As these numbers suggest, however, there are limits, and our forecast assumes that participation by age group never quite returns to the levels experienced in the mid-2000s. And while the forecast also assumes that labor force participation of older workers remains high, the aging of the population will eventually reduce the supply of workers without a significant boost in immigration. Routine monthly employment growth of 175,000—as experienced in 2019—is not likely to recur once the economy bounces back from the COVID-19 outbreak.

Immigration reform might have a marginal impact on the labor force. According to the Pew Research Center, undocumented immigrants make up about 4.8 percent of the total American labor force.22 Immigration reform that restricts immigration and/or increases the removal of undocumented workers might create labor shortages in certain industries, such as agriculture, in which (according to Pew) a quarter of workers are unauthorized, and construction, in which an estimated 15 percent of workers are unauthorized. But it would likely have little significant impact at the aggregate level.

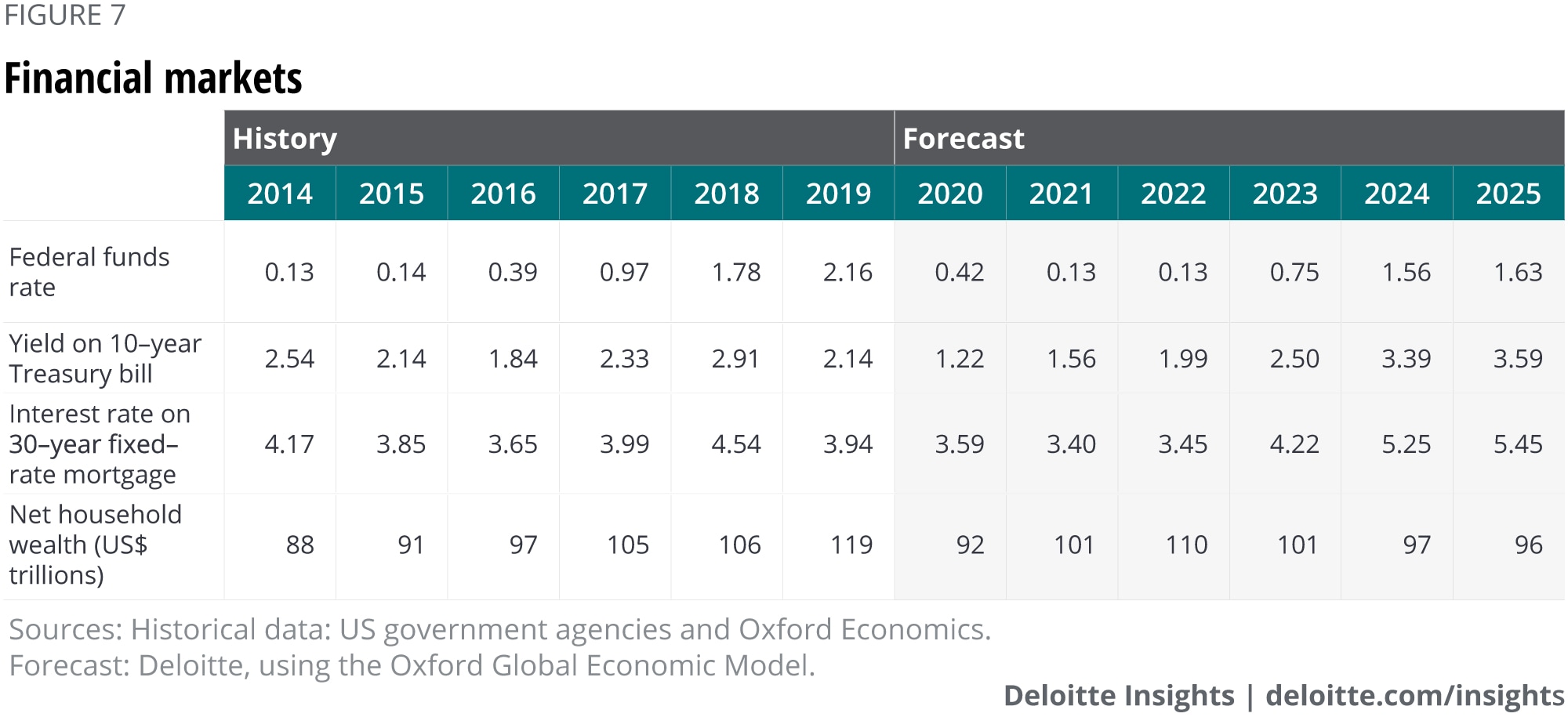

Financial markets

Interest rates are always the least certain part of any forecast. Interest rate movements (like stock prices) depend on news. And the news has been driving interest rates both down and up. How could that be? Risk-free interest rates, like those on Treasury bonds, have been driven down to record lows. That reflects investors’ desire to hold assets of an entity which they know won’t default. But interest rates on riskier assets—especially high-yield corporate bonds—have been driven up. Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, investors were looking for return, and the high-yield bonds delivered that return. But many of the companies that issued those high-yield bonds are about to experience steep declines in revenues. Can they repay? Investors are beginning to wonder. That’s why they are dumping those bonds.

But the Fed has made the immediate prospect for short-term rates clear: They will be very low. The Fed is most likely not trying to stimulate economic activity through low interest rates. That would be difficult, particularly since the COVID-19 outbreak is not going to be offset by more consumer and business purchases of durable goods and investment structures and equipment. What’s more important is keeping credit markets from simply stopping. Businesses that need cash, and households that wish to purchase big-ticket items rely on functioning financial markets. Lower interest rates are one part of the Fed’s formula to keep financial markets working. Beyond them, the Fed is rolling out other measures as necessary. These include (as of mid-March) a renewal of quantitative easing (purchasing long-term bonds), a lending program to keep the commercial paper market functioning, and a lending program to help keep primary dealers afloat.

The Fed’s actions highlight the short-term financial risks to the economy. Unavoidably, the COVID-19 outbreak will create a downturn. But the size of that downturn may depend critically on whether financial markets continue to function—or freeze up. In 2008, the freezing up of financial markets helped to make the recession particularly deep. The Fed—and everybody else—would like to prevent this from happening again.

Long-term interest rates remain very low by historical standards. This is a global problem, with a substantial number of countries—including economic powerhouses such as Germany and Japan—paying negative interest rates. This has made a standard way of thinking about “normal” interest rates obsolete. It used to be a kind of rule of thumb that, in the medium term, a full-employment economy would see a spread of about 200 basis points between the short- and long-term rates. Previous Deloitte forecasts assumed that the Fed would raise short-term rates to the 2.5 percent or even 3.0 percent level, above the targeted 2.0 percent rate of inflation. That argued for the key long-term rate in the forecast—the 10-year Treasury note yield—to move to 4.5 or 5.0 percent.

This is becoming very unlikely over the next few years. The current baseline assume that long-term US interest rates settle in at an equilibrium rate of around 3.0 percent during the five-year forecast horizon. This is lower than we previously forecast, and lower than historical experience would suggest.

However, it’s hard to argue with the current state of financial markets—including falling long-term risk-free interest rates and (at such low rates) low demand for funds to finance investment projects over the past several years.

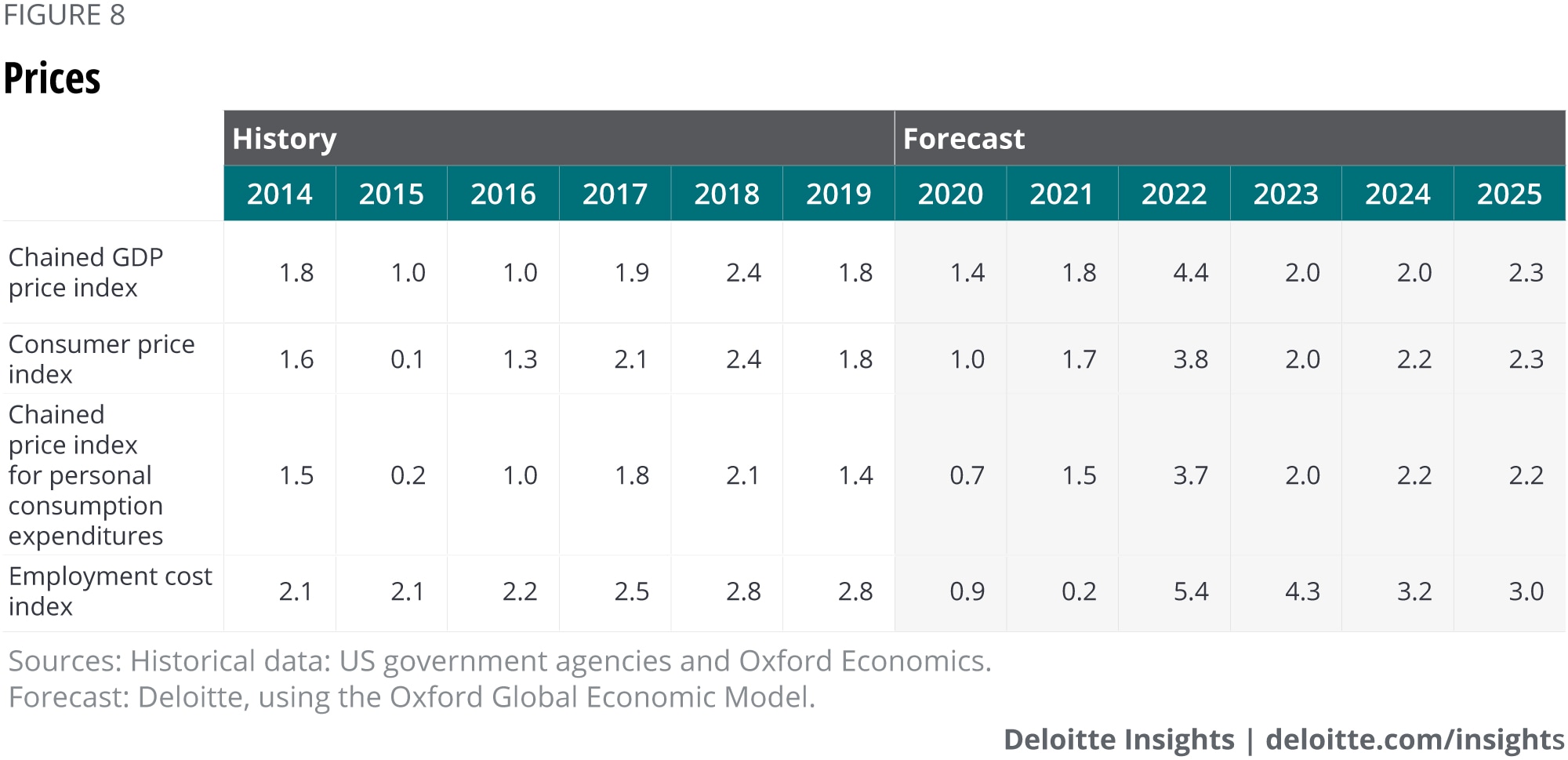

Prices

COVID-19 may have quirky and very specific impacts on prices. The drop in oil prices, for example, is likely to eventually be felt at the pump. That may be welcome as some other prices (for personal-care items, for example) rise. Don’t be fooled by idiosyncratic changes in inflation: The underlying inflation rate will remain under control—and perhaps a bit too low.

In fact, it’s been a long time since inflation has posed a problem for American policymakers. Could inflation break out if the economy bounces back and reaches full employment? Many economists are increasingly wondering about this, as it becomes ever more evident that something is amiss in the standard inflation models. These models posit that, since labor accounts for about 70 percent of business costs, tight labor markets driving higher wages would be the main cause of rising inflation. By traditional measures, the US labor market is tight. Unit labor costs have been accelerating, but at 3.0 percent, they are still growing at a moderate pace.

At some point, however, economic growth and the robust labor market could push the economy into a real labor shortage. And tariffs are something of a wild card. Although most of the tariffs have been on intermediate products, there is evidence that the additional cost was simply passed through to final consumers.23 The most recent tariff increase included more consumer goods and may be felt directly in the CPI.

A return to 1970s-style inflation is about as likely as polyester leisure suits coming back into style. But it would not be surprising in these circumstances to see the core CPI rise to above 2.5 percent.

Appendix

More from the Economics collection

-

A view from London Article2 days ago

-

The economic impact of COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) Article4 years ago

-

Asian consumers Article4 years ago

-

How do Americans spend their time? Infographic6 years ago

-

Retirees of the future Article5 years ago