How the virtual health landscape is shifting in a rapidly changing world Findings from the Deloitte 2020 Survey of US Physicians

19 minute read

10 July 2020

Ken Abrams, MD, MBA United States

Ken Abrams, MD, MBA United States Urvi Shah United States

Urvi Shah United States- Casey Korba United States

Natasha Elsner United States

Natasha Elsner United States

COVID-19 changed orthodoxies and pushed physicians to adopt virtual health. It’s time for health care systems to redefine conventions, consolidate the learnings, and scale up what worked to achieve a seamless patient and physician experience.

Executive summary

Virtual health offers great promise to transform care delivery by meeting patients where they are—on the road, at home, in a long-term care facility, or a remote intensive care unit—and expanding access to clinical expertise. As the health care landscape evolves, organizations should keep the patient at the center of the business model. This means making the patient-physician interaction seamless, convenient, and high quality.

Learn more

Explore the health care collection

Visit the health forward blog

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

From January 15–February 14, 2020, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions conducted its biennial survey of US physicians, which featured questions around physicians’ experience and perspectives on virtual health. This survey was conducted before COVID-19 significantly impacted the United States. Before COVID-19, most physicians were not intending to use many virtual health solutions, and those who were using virtual health were for the most part only gradually increasing their usage when compared to 2018. Few physicians in the survey reported clinical advantage as a top benefit to virtual health. When the US began responding to the pandemic, many of those orthodoxies appeared to change. The period of March through May 2020 saw an unprecedented shift to virtual health—fueled by regulatory flexibility and necessity. Even though our survey was fielded before the public health crisis, some of the challenges that physicians raised about using these technologies prior to the pandemic will continue to be instructive as health care systems develop their new virtual health strategies.

Our survey showed that before COVID-19 was impacting the country:

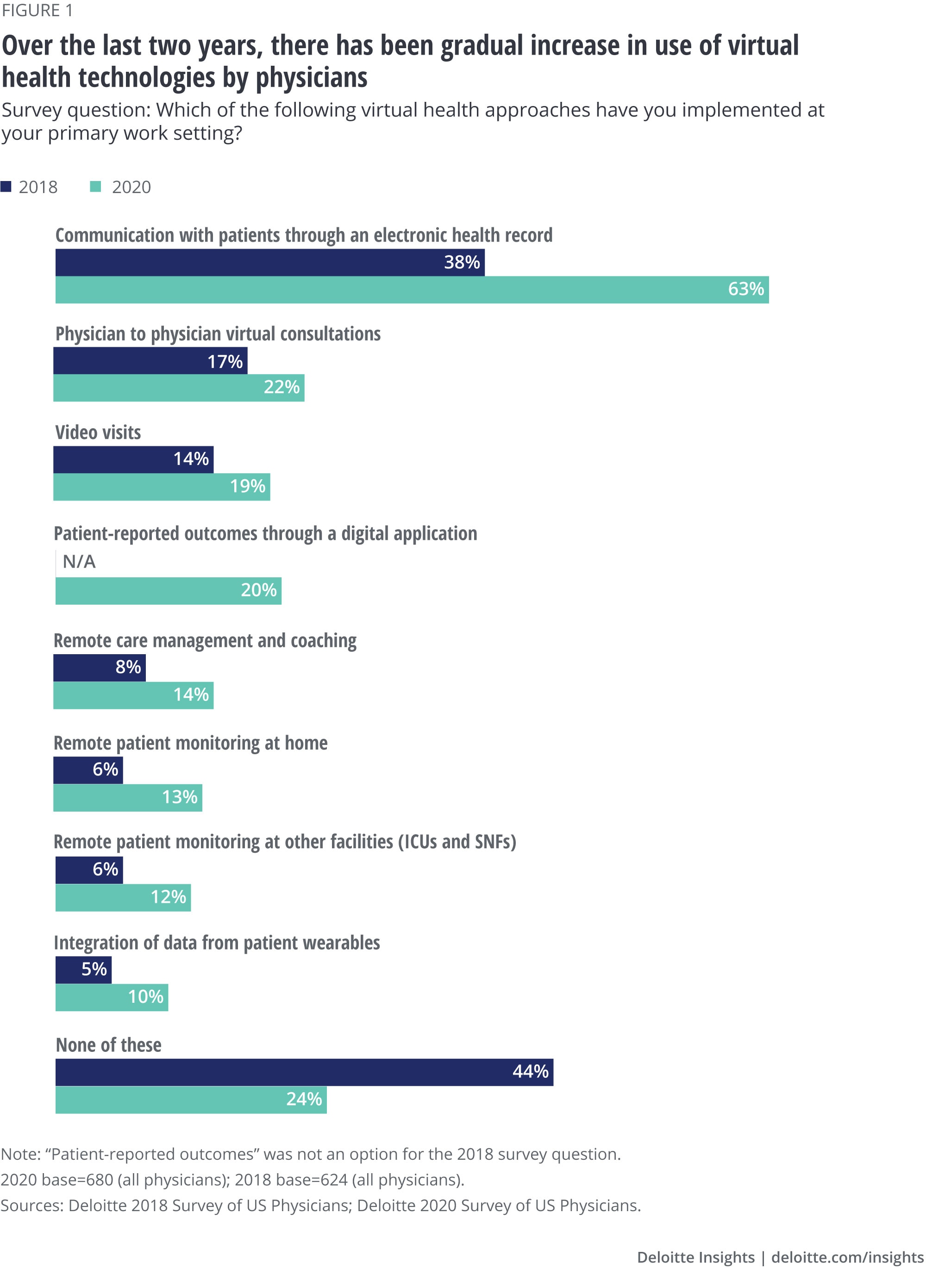

- Physicians were gradually increasing their use of virtual health. We saw gradual increases in physician-to-physician consultations (from 17% in 2018 to 22% in early 2020) and virtual visits (from 14% in 2018 to 19%). Remote care monitoring and coaching also saw a small increase. One exception was the increase in the proportion of physicians communicating with patients through the electronic health record (EHR), which grew from 38% in 2018 to 63% in early 2020.

- Most physicians (90%) said essential factors for virtual health were absent in their practices. Physicians deemed training on how to improve practice revenue with virtual health, adequate reimbursement for virtual health, and understanding regulations around virtual health essential, but lacking. Similarly, 85% of physicians cited training around improving skills such as conveying empathy in virtual visits as also essential, but absent in their practice.

- Physicians were looking ahead to radical interoperability, changing business models, and an increased emphasis on prevention and well-being. Physicians were betting on radical interoperability in the next 5–10 years, and on the streamlining of data and integration of data from wearables. Most physicians believe that the next generation of doctors should have a good understanding of the business of medicine and a robust knowledge base in prevention and well-being.

Since we fielded our survey, COVID-19 has dramatically reshaped the landscape. Data from the spring of 2020 shows more physicians are using virtual health1 (with some practices reporting a 50%–70% increase in use).2 As the initial response phase passes, virtual health is poised to become a central part of the health care delivery system. Patients and clinicians who have experienced the convenience of virtual health might not want to go back to in-person care for many types of visits.

Based on our survey data and early lessons learned from the virtual health landscape during the first few months of COVID-19, we offer recommendations on how health care stakeholders can facilitate and increase virtual health adoption. These include:

- Prioritizing training and continued learning: Virtual health is driving changes in how physicians communicate and treat patients, and has implications on workflow, practice revenue, and medical liability. But most surveyed physicians said critical information and training were not available in their practice.

- Integrating data and automating processes: It is critical that virtual visits and other virtual solutions are as easy for the clinician and the patient as traditional encounters. Almost all (84%) physicians said that ease of use and seamless integration of technology are essential, yet 82% said these elements were lacking in their practice. Our survey shows that physicians expect integrated data at scale in the coming years. Physicians are going to likely need support evolving operations and workflow as virtual health accelerates.

- Redefining traditional “best practices” and scaling up what worked: During the early response phase of the COVID-19 crisis, many health systems and physician practices rapidly implemented processes around virtual health. While consumers might be forgiving of flawed experiences with virtual visits or virtual health solutions during the crisis, they will likely expect refinement with time. As organizations move out of the initial response phase and begin to recover and ultimately thrive3 in the coming months and years, they should work to thoughtfully consider which traditional best practices aren’t working anymore, and scale up new learnings that will help them transition to a longer-term approach.

Methodology

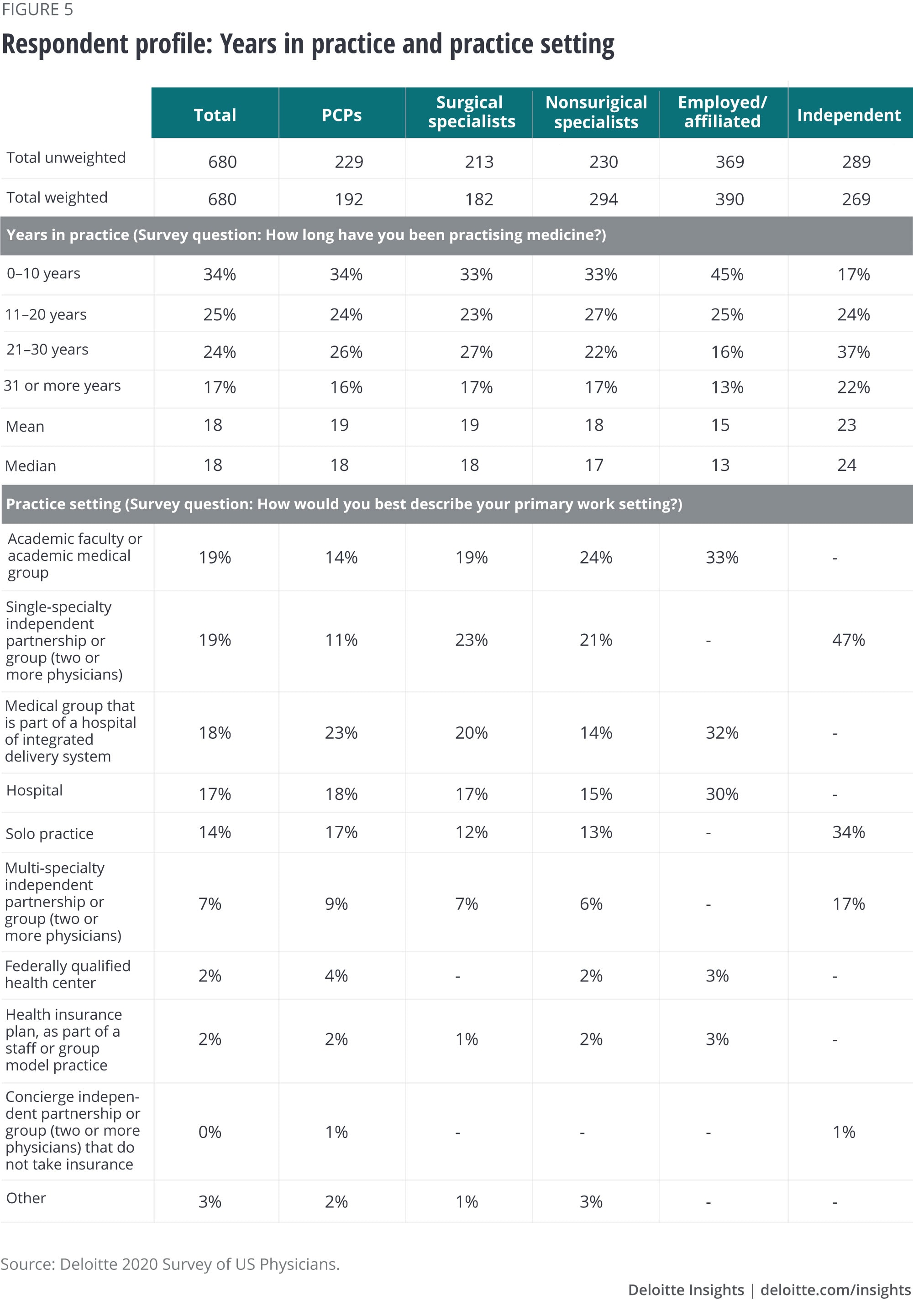

The Deloitte Center for Health Solutions fielded its biennial survey of US physicians, performed since 2011, from January 15–February 14, 2020. This survey of 680 physicians is nationally representative of US primary care and specialty physicians with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty. See the Appendix for detailed information on our sample.

In early 2020, physicians were gradually increasing their use of virtual health

Prior to COVID-19, our survey showed a gradual increase in physicians’ use of virtual health since 2018 (figure 1). Physician-to-physician consultations grew from 17% in 2018 to 22% in early 2020. While 14% of physicians in 2018 had conducted virtual visits, 19% reported doing so in early 2020. For primary care physicians, remote care management and coaching grew from 11% in 2018 to 21% in early 2020 (over the entire sample including surgical and nonsurgical specialists, the increase was eight percentage points to 14%). Remote monitoring at home and integrating data from patient wearables were also trending upward, especially among primary care physicians.

One exception is the proportion of physicians communicating with patients through the EHR—38% in 2018 versus 63% in early 2020. Communicating through the EHR could include posting test results or notes from the visit to the patient portal or answering quick questions through email.

With some early data from the COVID-19 response period showing that more physicians are using virtual visits, now that more physicians have experience with it, how might this accelerate use? While prior Deloitte research4 has shown that care has been shifting out of the hospital for years, when COVID-19 began causing a surge in patients, there was an increased demand for remote monitoring tools that could keep lower-risk patients at home while still giving them the care and monitoring they needed (see sidebar, “Case study 1. Accelerating virtual health in action—Chatbots for screening and intake”).5 As health systems work to keep patients safe from infection in the coming months, including how to keep patients at a safe distance in waiting rooms and other areas, many will likely want to think about how to keep healthy patients separate from patients who might be sick.

Virtual visits and monitoring patients’ blood pressure, breathing, and temperature, as well as the functioning of their lungs, heart, and other vital organs, are all possible from home. During the response phase of the crisis, some health systems had to direct their efforts to rapidly deploying new and untested methods. As they move into the recover and thrive6 phase, the focus will shift to making sure physicians and patients are adequately trained to use these tools and integrating them with other parts of a hospital’s technology infrastructure, including electronic record keeping systems.7

Case study 1. Accelerating virtual health in action—Chatbots for screening and intake

Before patients arrive in the emergency department, health systems can identify and triage patients with COVID-19 symptoms using automated screening algorithms, reducing the strain on frontline response capabilities. Jefferson Health is using an artificial intelligence (AI)–powered chatbot, LifeLink, to refer moderate and high-risk patients to nurse triage lines and enable patients to schedule video visits with physicians.8 The tool helps optimize care utilization across the network. Previously, patient information was captured over phone calls or in-person interactions. With LifeLink, this information is captured using interactive messaging. Based on the information gathered, LifeLink conducts a risk assessment of the patients. Additionally, the chatbot is designed to integrate with EMR, customer relationship management (CRM), and other scheduling systems, which helps improve care outcomes and patient experience.9

Physician intent to use virtual health was growing gradually prior to COVID-19

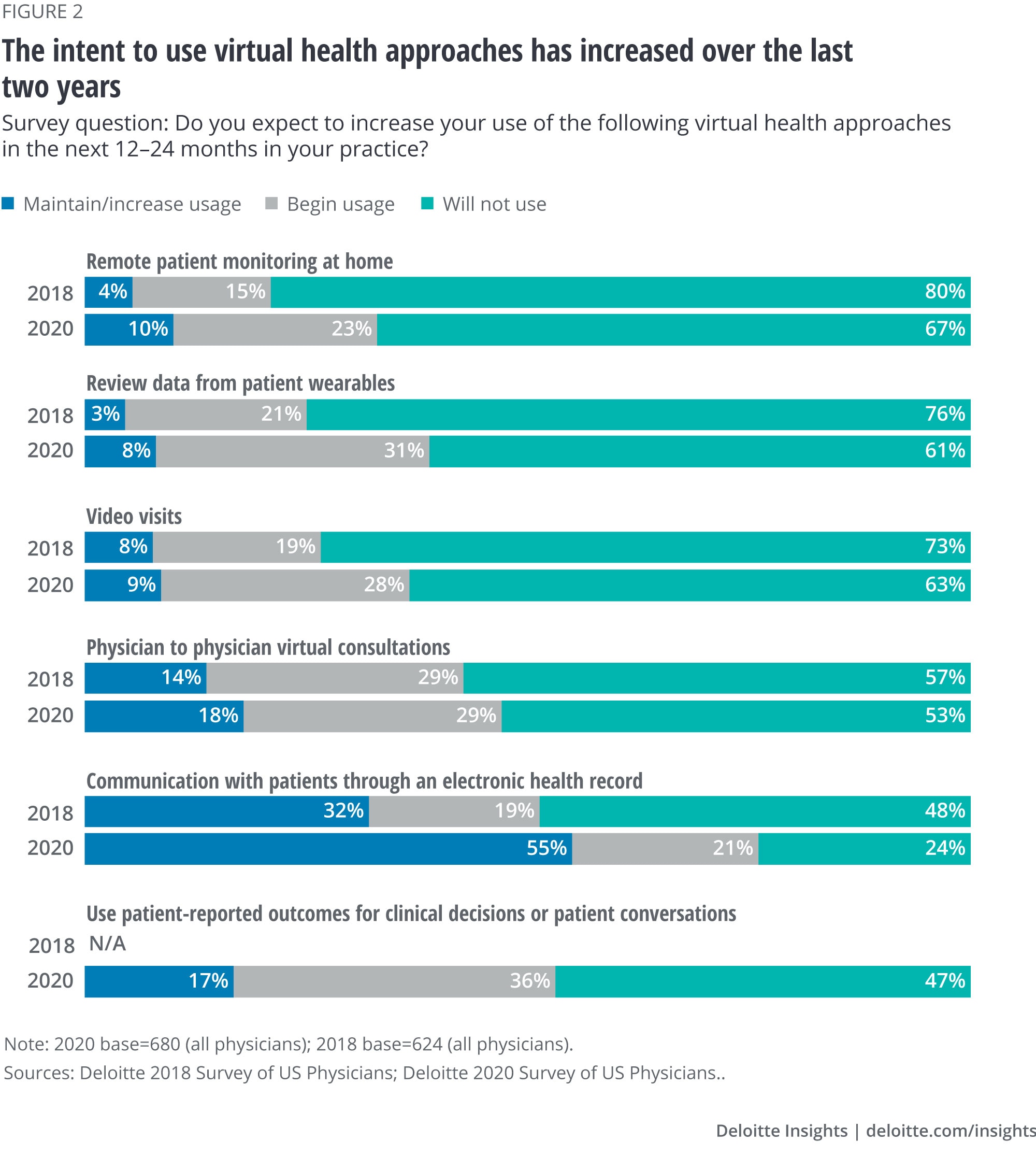

The intent to use remote monitoring at home increased from 20% of physicians in 2018 to 33% in early 2020 (figure 2). Thirty-seven percent of physicians were planning on using video visits (up from 27% in 2018), and more physicians intended to review data from wearables than in 2018. These results point to a declining physician resistance to virtual health over time. One study looking at virtual visits in one health system saw virtual urgent care visits grew by 683% in a six-week period between early March and mid-April and a 4,345% increase in nonurgent virtual visits during that same period.10

This data suggests that though physicians were reluctant to engage in virtual health before the pandemic, their attitudes changed with COVID-19. But what needs to happen for this to continue? Our survey findings provide one clue: Physicians who have bonus payments tied to specific performance goals reported greater adoption of virtual health. Compared to those not receiving performance-based bonus payments, these physicians were more likely to:

- Have physician-to-physician virtual consultations (27% vs. 16%)

- Conduct video visits (22% vs. 14%)

- Participate in remote care management and coaching (16% vs. 11%)

Greater use of value-based models could provide the incentive for providers to expand virtual health offerings.

What value-based care models might health systems and health plans look to as face-to-face visits ramp up again? And what percentage of visits will take place virtually as we continue to recover from the pandemic in the coming months? Prior Deloitte research has shown that younger people are interested in increasing virtual visits and this trend will probably accelerate. Older people, at high risk of complications from the virus, might be more likely to opt for virtual visits and remote monitoring solutions. With lessons learned from the past few months and changes in demand, health care organizations might need to rethink what care is appropriate for virtual interactions and what truly requires face-to-face visits. It might be too early for definitive answers, but we know from our survey data that regardless of demand, there are certain issues that should be addressed for physicians to continue to embrace virtual health. Redefining and scaling up what works, training on changing business models and effective communication during virtual visits, and clarity around regulations all should be in place to ensure that the acceleration of virtual health gives us the best health outcomes and patient experiences.

Virtual health + virtual work could innovate workflow, care delivery

Virtual visits have clearly taken off in the last few months, while at the same time, more Americans work from home to stay safe. It’s possible that health systems can tap into a workforce that was previously not willing or able to commute to hospitals and facilities, such as clinicians who want flexibility or who want to work nontraditional hours. As the pandemic subsides, some health systems might want to retain these kinds of workers to offer more options for patients.

With a virtual visit, it is also possible for family caregivers to participate, even if they are in a different location than the patient and provider. Caregiver participation could lead to better adherence to medication and lifestyle regimens, and could strengthen patient understanding of what they need to stay healthy, and bolster their support system.

These new ways of working and interacting with patients and their families could lead to innovations in how we manage certain populations and could ultimately lead to better outcomes and a better patient experience.

Essential elements such as training, reimbursement, and clarity around regulations were absent in early 2020

Pre-COVID-19, approximately 90% of physicians said essential factors such as training on how to improve practice revenue with virtual health, adequate reimbursement for virtual health, and understanding regulations around virtual health were all absent in their practice. Eighty-five percent of physicians also reported that training on how to communicate effectively with patients using virtual means was essential for success, but lacking. Eighty-three percent said that patient demand was also essential but lacking (figure 3).

Conducting a high-quality virtual visit is not the same as having a face-to-face visit, and it is more complex than simply logging on to a screen. Physicians should get comfortable with the technology and learn tips for building rapport, showing empathy, and making eye contact in a virtual setting. New workflows might need to be developed for patient intake, history, and vitals, typically performed by medical assistants or a nurse in the office. Supports should be in place to troubleshoot technical glitches (whether on the patient or provider side) that can derail a virtual visit experience. The logistics of conducting virtual and in-person visits should be worked out to help ensure a seamless consumer experience. For example, Deloitte’s 2018 consumer survey data showed that consumers saw room for improvement with their experience with virtual visits, citing concerns such as having to wait for the visit to start, and not feeling like they received all the information they needed from the visit.11 Health systems should decide if it is better to have dedicated virtualists, or have a hybrid approach, with physicians spending part of their time in the office and part of their time online. Thinking through operating models and workflow will likely be critical.

During the first few months of COVID-19 response, we saw a huge uptake in the use of virtual health to keep patients home.12 What will patients expect from the health care system now that many have experienced virtual visits?

Of the physicians who considered patient demand essential for virtual health, most (83%) thought that in early 2020, patient demand for virtual health was absent. Positive experiences with virtual health today might mean tomorrow’s patients are less willing to take a day off work to travel for an in-person doctor visit. Deloitte’s consumer survey series shows that consumer interest in virtual health has steadily climbed in the last several years.13 Deloitte’s Study of Health Care Consumer Response to COVID-19 (conducted in April and May of 2020) shows that 84% of consumers who used virtual health reported they were satisfied with the experience, and four out of five consumers said they would be interested in using virtual health in the future.14 Consumers have shown the interest and demand is there, and physicians and health systems should think through how to meet this demand.

Data shows that prior to COVID-19 physicians largely hesitated to embrace new technologies and virtual health solutions. The promise of technology and automation offers hope that we will be able to free up physicians and other clinicians to practice at the top of their license and realize the vision of a system focused on health rather than one centered around acute health care. However, physicians want to be sure that any new technology or protocol is reliable, evidence-based, validated, and good for patients. They also want to know they will be able to implement the new model and get paid for it.

Looking ahead, while there is some regulatory uncertainty, many experts expect acceleration of virtual health as health systems strive to meet consumer demand and physicians become more familiar with the technology.

Enterprise implementation might look different from practice to practice and health system to health system, but several leading practices are worth keeping in mind:

- Hospitals and health systems should prioritize a system that can enable all caregivers to practice at the top of their license and affirms physicians as partners in care rather than employees to be managed.

- When developing criteria for specific technology investments, organizations should include physician time and workflow in addition to business value.

- Organization leaders should consider investing in training tools that can help clinicians feel confident about their changing role and translate their bedside manner over the screen.15

- Credentialing is another issue health systems should consider. Physicians and clinicians should be appropriately credentialed in the states they practice. The credentialing system should be modernized to adapt to virtual visits. Cloud-based credentialing technology can help health systems and health plans modernize their systems.

Case study 2: Accelerated virtual health in action—Video visits

A common challenge faced by health systems tackling COVID-19 is to protect physicians and staff from exposure while treating patients. Telehealth has presented itself as a compelling solution. Geisinger Health has partnered with Teladoc to provide physician consultation for patients from home.16 The benefit is not limited to COVID-19-related cases: Members can use Teladoc for any routine medical need. Members can set up virtual consultation by making a request online (via the app) or through a phone call. In anticipation of increased demand for telehealth visits, Geisinger Health trained over 1,000 providers to conduct virtual visits with patients.17 Additionally, physicians have been provided with devices, cameras, and headsets to work from home.

What can we learn from the rapidly changing regulatory landscape?

Certain regulations were temporarily lifted during the “respond” phase of the crisis. As the public health emergency calms down and health systems begin to recover from the initial crisis phase, how will regulators respond?

To help Americans stay safe while getting access to health care, the US Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services(CMS) and the Trump administration made many temporary changes to telehealth regulations during the crisis when many Americans were staying home. By declaring a public health emergency, the secretary of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) was given the authority to waive certain telehealth restrictions for the duration of the emergency, and CMS gave other flexibilities through waivers provided in the CARES Act18 and through emergency rule-making. These regulatory flexibilities will last until the “end of the public health emergency,” as determined by the federal government. Most changes are applied to Medicare fee-for-service payment policies. Although there was flexibility given to Medicare Advantage and Medicaid, the health plan or the state generally sets Medicaid payment policies.

The flexibility is focused on:

- Removing requirements that a patient must be an established one before initiating a virtual visit and receiving remote monitoring services, and allowing payment for smart phones and audio-only phone calls

- Modifying and simplifying consent forms and allowing telehealth visits to take place in both the patient’s and the clinician’s home

- Payment parity for virtual or telephone visits

- Payment to many types of practitioners (including allied health professionals)

- Encouraging states to use virtual health in Medicaid

While the flexibilities are tied to the pandemic and will likely be pulled back or modified when the public health emergency is declared over, many expect CMS to use the normal rule-making process to take into consideration what was learned during the emergency and what flexibilities should be adopted moving forward.

Case study 3: Accelerated virtual health in action—Tele-ICUs

As health systems run into staffing capacity issues, some of them are using tele-ICU to monitor patients. Tele-ICUs usually consist of two-way bedside video feeds between clinicians and patients who are both in different locations. Using high-definition cameras, clinicians located in a command center can visually monitor patient vitals. This enables hospitals to save time and efficiently manage resources. Northwell Health has implemented tele-ICUs to manage COVID-19 patients. Clinicians at Northwell Health’s telehealth command center are monitoring more than 170 ICU beds across 10 hospitals, with plans to expand to 300 beds by the end of the year. Clinicians sit in front of monitors that connect them to patients via two-way video conferencing. They track patients’ vital signs and are alerted by the system to intervene, if required.19

Physicians in our survey were looking ahead—will their vision materialize sooner than expected?

We asked physicians responding to our survey to tell us what trends they expect will become standard practice in care delivery in the next five to 10 years. Our findings aligned with the Deloitte survey of health care executives, who were members and partners of the ATA (American Telemedicine Association).20 We fielded the executive survey around the same pre-COVID-19 period as the physician survey. Both physicians and health care executives were willing to bet on radical interoperability in the next five to 10 years, and were bullish that patient data from wearables would be integrated with health care delivery (figure 4).

Most physicians in our survey believe that the next generation of physicians should focus on understanding the business of medicine (65%) and how to deliver care that focuses on prevention and well-being (59%). Physicians responding to our survey said that the health care landscape is changing, and that the next five to 10 years would look very different. In Deloitte’s vision for the future of health, we expect an increased emphasis on strategies around prevention and well-being to keep people out of the hospital. With the shift from volume to value, health systems are beginning to devote resources to caring for patients at home when possible.21 The transition from a sick/acute care system to a system focused on health was happening pre-COVID-19, but now the need for personalized and preemptive care with genomics, sensors, and AI-based digital therapies has been accelerated.

Virtual health is accelerating: Implications for health systems

Before COVID-19 disrupted our lives, the US health care system was on the path of a major (albeit gradual) evolution due to the shift from volume to value, consumer demand for services that were as convenient and curated as those of major retailers and technology companies, and unsustainable costs. The pandemic has accelerated this evolution, and the future of health is arriving much sooner than we thought. Virtual health is at a tipping point, and in 20 years, we might look back at this moment in our history as the catalyst for acceleration. As health care systems adapt to a new normal, and continue to respond, recover, and eventually aim to thrive in the new landscape, what virtual health strategies should be top of mind?

- Prioritize training and continued learning: Our baseline data showed that health systems, even before the pandemic, needed to focus on training to encourage physician adoption of virtual health: training around translating their bedside manner to virtual visits and improving skills such as conveying empathy through the screen, as well as training on how to improve practice revenue with virtual health. These needs remain and will now likely be accelerated due to increased demand.

- Integrate and automate: Health systems should have strategies around integrating automation and technology. Health systems and vendors should work to ensure that virtual visits and other virtual health solutions are as easy to deliver as traditional encounters and should consider seamless integration with the EHR and workflow redesign to address these needs. It will also be important to help ensure that clinicians can practice at the top of their license and that their needs are considered as well as the patients.

- Revisit what was put in place during the crisis and decide what to thoughtfully scale up: Virtual health programs put in place during the crisis were focused on meeting short-term, urgent needs. In the long term, however, that approach can lead to tailored processes limited to single-use cases rather than allowing for flexible protocols that adapt with time. Health care organizations should continually reassess their virtual health programs in the coming months to verify that an enterprisewide strategy, appropriate governance models, workforce training, and other infrastructure are in place for long-term integration and success.

Appendix: Study methodology—2020 Survey of US Physicians

Since 2011, the Deloitte Center for Health Solutions has surveyed a nationally representative sample of US physicians on their attitudes and perceptions about the current market trends impacting medicine and the future state of the practice of medicine.

The general aim of the survey is to understand physician adoption and perception of key market trends of interest to the health care, life sciences, and government sectors. In 2020, 680 US primary care and specialty physicians were asked about a range of topics: virtual health, digital technologies, future of work, and value-based care.

We selected a random sample of physician records with complete mailing information from the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, and stratified it by physician specialty, to invite participation in an online 20-minute survey.

The resulting study sample is representative of the AMA Masterfile with respect to years in practice, gender, geography, practice type, and specialty to reflect the national distribution of US physicians.

Data collection took place between January 15 and February 14, 2020.

About the AMA

The AMA is the major association for US physicians and its Masterfile is a census of all US physicians (not just AMA members). The database contains records of more than 1.4 million US physicians and is based upon graduating medical school and specialty certification records. It is used for both state and federal credentialing, as well as for licensure purposes. This database is widely regarded as the gold standard for health policy work among primary care physicians and specialists, and is the source used by the federal government and academic researchers for survey studies among physicians.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

Explore more

-

The future of virtual health Article4 years ago

-

Medicaid in 2040 Article5 years ago

-

The economic impact of COVID-19 (novel coronavirus) Article5 years ago

-

Cell and gene therapies Article4 years ago

-

The future of biopharma Article5 years ago