Perspectives

The Challenge of Double Materiality

Sustainability Reporting at a Crossroad

One of the more significant announcements at the COP26 meetings in Glasgow in November concerned the launch of the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) by the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) Foundation1.

The creation of the ISSB has been in the pipeline for a while, but the COP26 announcement included the news that the Value Reporting Foundation and the Climate Disclosure Standards Board will be consolidated into the new board. The Value Reporting Foundation consists in turn of both Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB) and the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC).

This means that four of the top five sustainability reporting organizations are now working in a coordinated way on a benchmark reporting standard. Given its backing from the accounting profession, its absorption of several leading reporting standards bodies, along with its favourable reception by governments, financial regulatory bodies and the involvement of the World Economic Forum, the ISSB is most likely to become the leading standard for reporting sustainability, and to become adopted as the basis for mandatory reporting in many jurisdictions.

It will be important to watch the detail of this unfolding process. The organizations that have consolidated into the new board emphasize their role in investor-focused sustainability disclosure driven by a responsibility to ensure good information and minimize risk to lenders, investors and insurers. This is in keeping with the IFRS Foundation’s role as a body set up to promote the reporting of information that could create or erode enterprise value.

For a company to report to investors, lenders or insurers is of course only part of the picture when it comes to creating mechanisms to enable responsible corporate conduct towards the environment and society.

Investor focus vs public concerns

As well as understanding environmental and social influence on a company’s value, regulators, consumers and society as a whole should also be able to understand each company’s impact on the environment and social wellbeing. These are not the same thing, because poor conduct by a company may not affect financial returns in the short, medium or even long term despite it being unacceptable in the realm of sustainable development. In fact, historical evidence of this is plentiful: because of society’s systemic failure to internalize environmental and social costs, poor corporate conduct on environmental and social matters has sometimes been rewarded with higher corporate profits or higher investment returns at the expense of the deterioration of planetary resources and social equity.

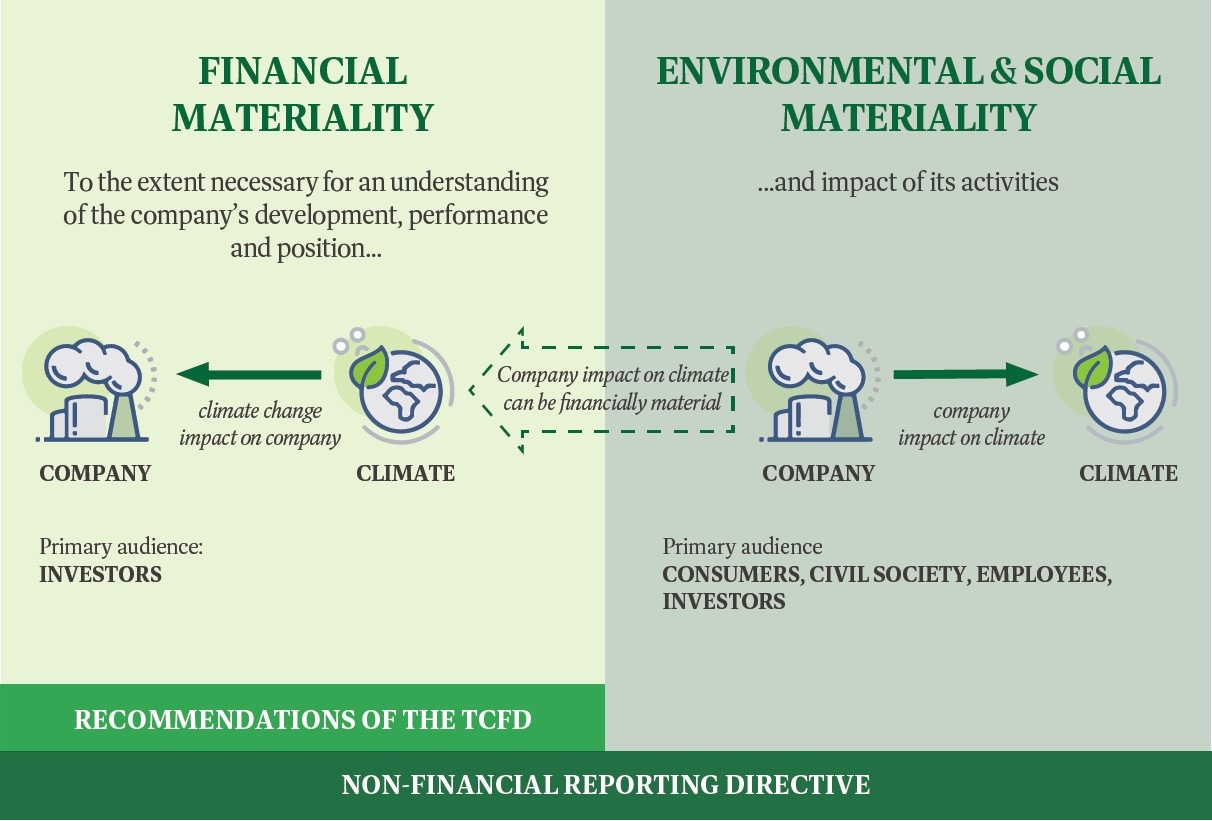

The European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation2, adopted in 2019, requires investors to disclose not only risks to themselves, but also their adverse impacts on both the planet and society. This ‘double materiality’ concept acknowledges the fact that risks and opportunities can be material from both a financial and non-financial perspective. Double materiality recognizes that companies and financial institutions must manage and take responsibility for the actual and potential adverse impacts of their decisions on people, society and the environment.

The EU Green Taxonomy3 and Guidelines on Reporting Climate-Related Information4 confirm double materiality as the basis for comprehensive non-financial information disclosure. The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), on schedule for implementation in 2023, will also incorporate double materiality5.

Figure 1: The double materiality perspective of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive in the context of reporting climate-related information

Source: New Guidelines on Reporting Climate-Related Information, European Commission(See note 4)

Decision time for corporate disclosure

The European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG) Project Task Force leading the technical work developing CSRD standards, announced a Statement of Cooperation with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) in July 20216. The GRI is the most widely used ESG reporting standard in the business world, but GRI is the one significant reporting organization not consolidated into plans for the ISSB. The application of ‘double materiality’ has always been a central theme for GRI since its inception, largely due to the fact that its development is based on a multi-stakeholder approach in which trade unions and civil society groups have significant influence.

So as ISSB moves to centre stage, one question will need to be answered: should sustainability reporting become largely a tool for investors to minimize risk and seek financial opportunities; or should it serve as a deeper indicator of corporate responsibility,ensuring companies act in the broader, long-term interests of society? Will governments and regulatory bodies adopting ISSB as a reporting standard be ready to ensure companies account for their impact on the wellbeing of all, or simply the wellbeing of their investors?

If ISSB is contemplating a weakened version of double materiality, this may encourage a migration from GRI to ISSB reporting standards. The business sector could be both sending and receiving the wrong signal: a company’s impact on the environment and society are secondary considerations compared to the environment’s financial impact on the company.

2 https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32019R2088

5 https://ksapa.org/new-csrd-revamps-european-financial-reporting/