Emerging Markets Outlook has been saved

Emerging Markets Outlook Present tense, future tense

7 minute read

24 September 2020

Emerging markets are in a tough spot.

Emerging market economies are facing numerous challenges, many of which are beyond their control. The health and economic costs of the pandemic have been severe in numerous countries. Even for countries that have avoided the worst outbreaks domestically, exports have weakened due to the fall in global demand. Emerging markets are also struggling to stimulate their economies. Governments and central banks have been necessarily cautious when providing fiscal and monetary stimulus to prevent financial disruptions. Despite relatively low fiscal stimulus, most emerging markets are facing much higher debt burdens due to the loss of revenue, which is adding to risks.

Learn more

Learn how to combat COVID-19 with resilience

Explore the Economics collection

Learn about Deloitte's services

Go straight to smart. Get the Deloitte Insights app

The rising cost of the pandemic

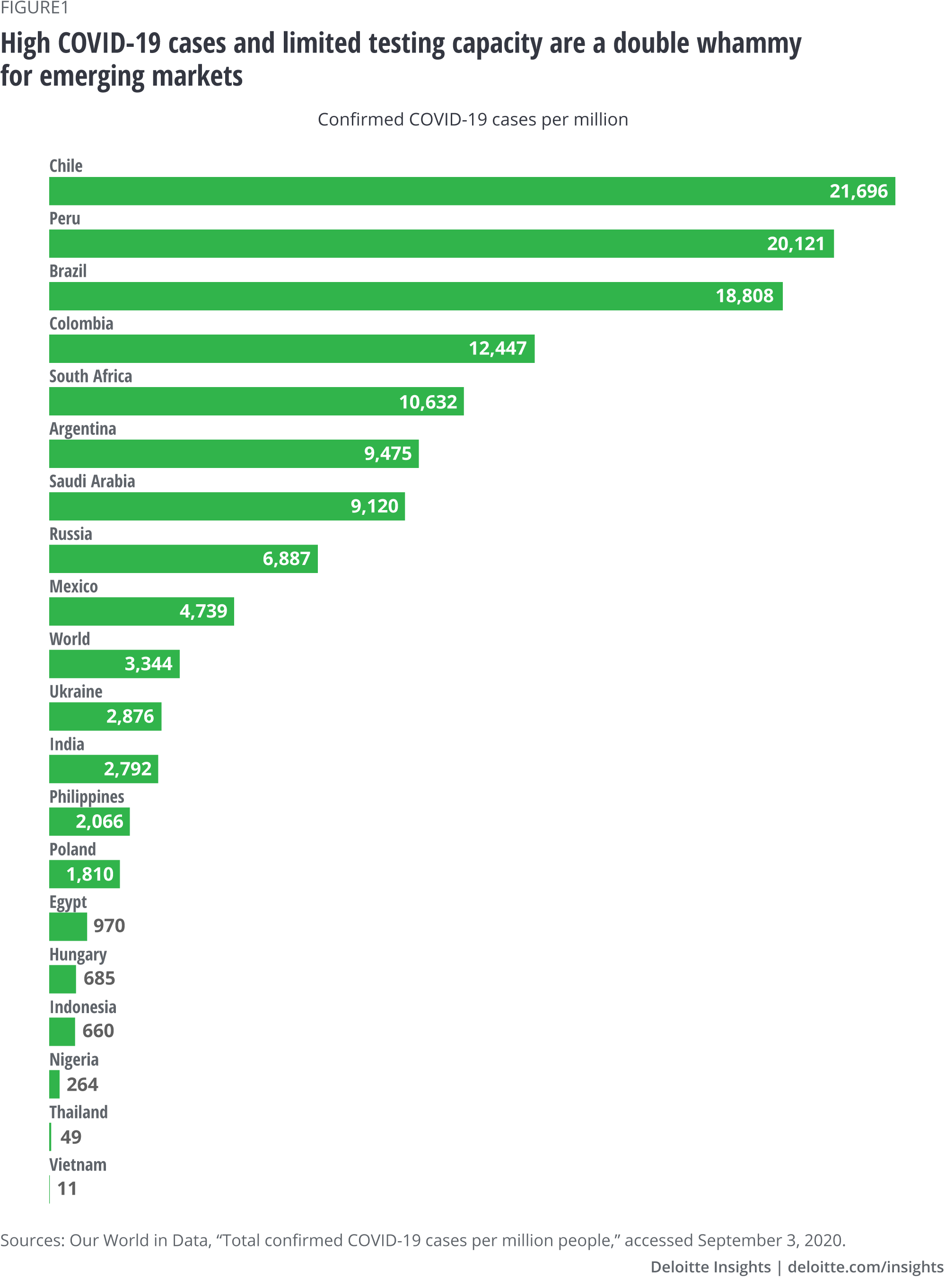

Many low- and middle-income countries, particularly those in Latin America, have had terrible COVID-19 outbreaks. Chile, Peru, Brazil, and Colombia have each had more than 10,000 confirmed cases per million people, among the worst in the world (figure 1). South Africa, Saudi Arabia, and Russia also had worse-than-average outbreaks after adjusting for population.1 Brazil, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines, which collectively have more than 2 billion people, had yet to contain their outbreaks by early September.2 However, a few emerging market countries have fared far better. Thailand, Nigeria, and Malaysia each had fewer than 500 confirmed cases per million people,3 besting South Korea and Japan. The number of actual cases may be higher as testing capacity is limited, particularly in Africa.4

As the pandemic hit and lockdowns were put in place, economic activity came to a halt. In some countries, the drop in real GDP was severe. Peru lost more than 30% of its output between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020.5 India lost more than 25%, while the Philippines, Colombia, Malaysia, Mexico, and Morocco each lost more than 15%.6 For comparison, the United States lost just over 10%. Only a few emerging market countries managed to see relatively small losses in the first half of the year. Vietnam stands out for posting just a 2.9% drop in real GDP.7

Dependence on external demand

Although the magnitude of the pandemic and the policy response are important factors for economic activity, what happens in the rest of the world has an outsized influence in low- and middle-income countries. A comparison of Brazil and Thailand provides a useful example. The number of confirmed cases in Brazil was more than 360 times higher than in Thailand after adjusting for population, and Brazil’s policy response has been more stringent than Thailand’s since the end of April.8 However, both countries saw their real GDP falling by 11.9% between Q4 2019 and Q2 2020.9 A large part of the problem for Thailand is that tourism accounts for more than 20% of its GDP, while it accounts for just over 8% in Brazil.10 Even if all borders were open, international tourism faces serious challenges during a pandemic. Countries that rely heavily on tourism, such as the Philippines, Lebanon, Mexico, and Morocco, will face similar issues until people can feel confident that they can travel safely.

In Brazil, a sizable depreciation of the currency and ample demand from China supported export growth. China’s ability to quickly get the virus under control and ramp up economic output helped support production in emerging market countries that typically export there. For example, Chile11 and Vietnam,12 where about 33% and 20% of all goods exports head to China, respectively, had already seen exports rise above their 2019 Q4 levels in dollar terms by June. Growth in China is expected to outpace that in the United States, which should continue to favor those emerging market countries with larger exposures to final demand in China.

The type of goods exported from each country has also been an important determinant of growth in the current crisis. Countries with large shares of technology-related exports, such as Malaysia, have seen export growth rebound more quickly. Higher prices of gold and copper have boosted exports from South Africa and Chile, respectively. However, energy exporters are still struggling with low prices and demand. Exports from Colombia13 and Russia14 were down 24.7% and 28.4%, respectively, in June relative to 2019 Q4. Saudi Arabia’s June exports were down 43.7% from a year earlier.15

Limits to stimulus

As countries struggle to navigate the change in demand outside their borders, stimulus measures can help boost domestic demand. However, low- and middle-income countries can run into problems quickly when trying to stimulate their economies. On the monetary side, lowering interest rates can raise inflation and lower the value of the currency. A weak exchange rate makes servicing foreign currency debts more difficult and can raise the cost of imports. Plus, it can be difficult for emerging markets to reinvigorate demand for their currencies once it has dried up. We saw this when recent US dollar depreciation came against hard currencies, such as the yen and euro, but emerging market currencies remained weak against the greenback at the same time.16 Central bankers are therefore cautious of easing too much lest they trigger higher inflation, which could force them to reverse course and tighten policy. A good example of this is India where the central bank has held the policy rate at 4% since May despite a severe recession taking hold. At the same time, headline inflation has accelerated above the targeted band.17 That inflation may be due to pandemic-related supply disruption, but it still forces the central bank to remain cautious when providing additional stimulus.

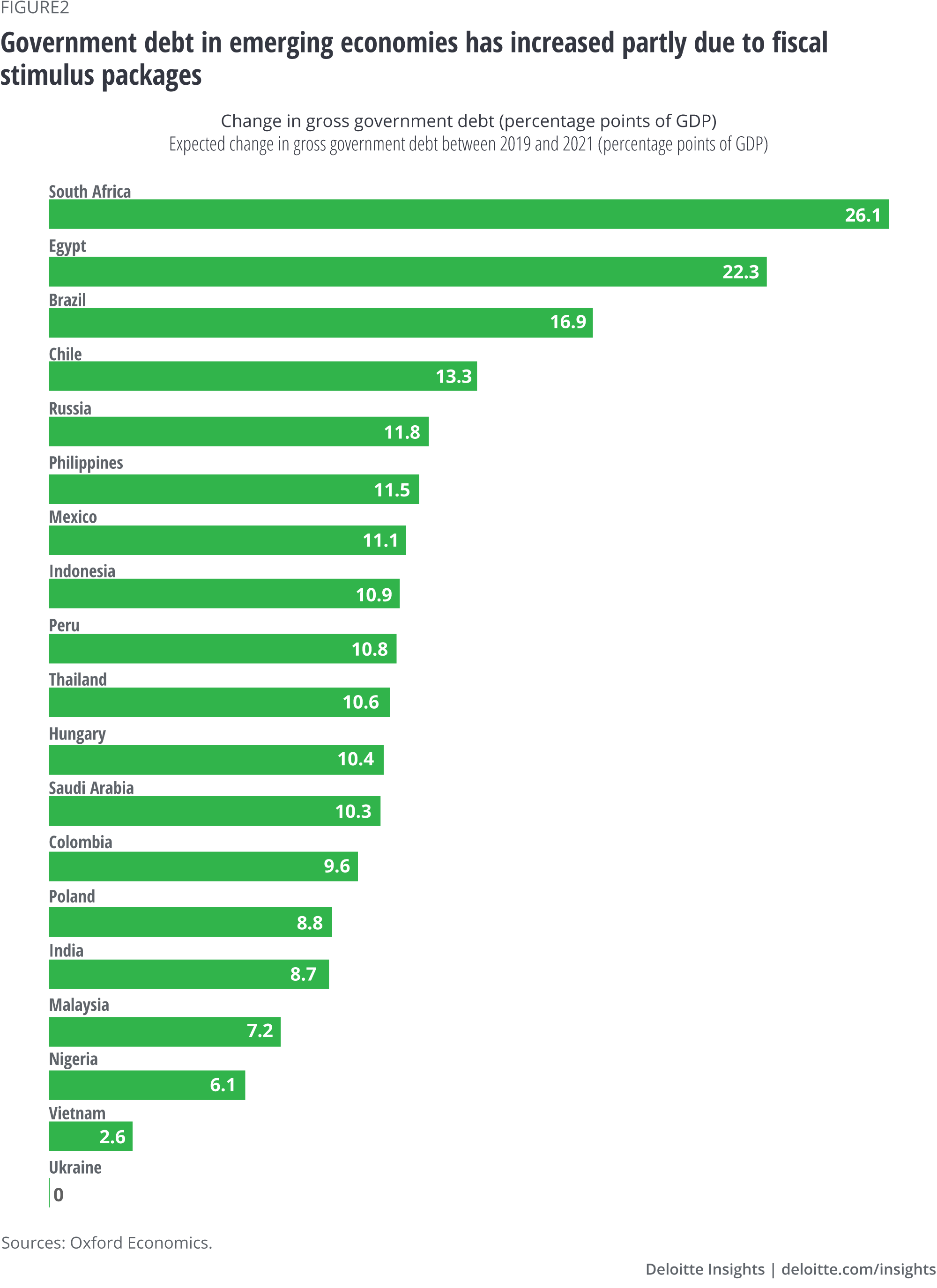

On the fiscal side, a similar issue appears. Additional financing can be hard to obtain if investors become concerned that debt levels are no longer sustainable. As a result, most emerging markets have implemented relatively modest stimulus programs. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimates that direct spending in India will amount to just 1.7% of GDP while Mexico’s stimulus will be just 0.7% of GDP.18 Even without much additional fiscal stimulus, countries’ fiscal positions have come under strain from the steep decline in revenue stemming from the slump in economic activity. For example, the consultancy Oxford Economics expects Mexico’s gross government debt as a share of GDP to rise by 11.1 percentage points between 2019 and 2021, and India’s by 8.7% (figure 2).19 Even larger debt gains are expected in the handful of countries that have announced more sizable stimulus packages, such as Brazil, Chile, Poland, and Thailand. So far, bond yields in these countries remain lower than they were at the end of last year, but higher interest rates could be on the horizon should investors begin to doubt the sustainability of these much-larger debt burdens. Higher government borrowing rates typically mean higher rates for the private sector, which is also in need of additional financing to cover costs during the pandemic. Higher borrowing costs will also come at the expense of business investment, which will weigh on productivity and longer-term economic growth.

So far, access to financing for emerging markets has been reasonably strong. The IMF, World Bank, and other multilateral institutions have stepped in to provide emergency financing, and the G20 suspended sovereign debt payments from many of the world’s poorest countries.20 The Fed has pumped substantial liquidity into global financial markets, and several middle-income countries, such as Saudi Arabia21 and Brazil,22 have still been able to issue sovereign bonds in international capital markets this year. However, the ability to service these rising debts remains questionable. Many emerging market countries’ sovereign debt is just barely in the investment-grade category.23 Another credit downgrade and they may find it even more difficult to find financing at sustainable interest rates. Although private portfolio flows have begun to return to emerging markets, they have been modest so far24 and could quickly turn to outflows once again should risks rise. Plus, the IMF estimates that emerging market governments have issued US$124 billion of hard currency debt in the first half of this year,25 making borrowers more vulnerable to exchange-rate depreciation.

Emerging markets have found themselves in a tough spot. External factors, such as the pandemic and weak global demand, have caused severe economic contractions. Stimulus has had to be modest in most cases, leaving these countries with few good options. Each country’s financial position coming into the crisis as well as the type and destination of its exports will help determine how it fares in the recovery. Businesses operating in emerging market countries will face the potential challenges of uneven demand, commodity price swings, and financial market volatility as the global economy attempts to get back on its feet.

© 2021. See Terms of Use for more information.

More from the Economics collection

-

Asia’s economic recovery Article4 years ago

-

Japan economic outlook, February 2025 Article2 months ago

-

India economic outlook, January 2025 Article3 months ago

-

Asian consumers Article5 years ago

-

China’s investment management opportunity Article5 years ago

-

Monetary policy in emerging economies Article5 years ago