Monetary policy in advanced economies Low policy rates are here to stay

8 minute read

18 October 2019

As the growth outlook dims and inflation remains below target levels, interest rates in advanced economies are likely to remain low. This is not without risks though. And it leaves central banks with less room to counter any future downturn than in previous recessions.

The suggestion that investors ought to pay rather than earn from their investments may seem outrageous. Well, it shouldn’t anymore. Because more than US$17 trillion worth of debt across the globe was yielding negative returns by the end of August 2019.1 And this was before the European Central Bank (ECB) pushed its deposit facility rate further down by 10 basis points (bps) to –0.5 percent in September.2 The ECB is, of course, not alone in the negative interest rate setting; it has other advanced economies’ central banks—including the Bank of Japan (BOJ), the Swiss National Bank (SNB), and Sweden’s Riksbank—for company.3 Negative rates, in fact, are part of a trend where central banks in advanced economies are either continuing with existing loose monetary policy or cutting rates as the growth outlook dims and inflation remains below target. In the United States, for example, the Federal Reserve reversed from its rate-hike path in July, cutting the federal funds rate by 25 bps and followed that with a similar cut in September.4 Only the Bank of England (BOE) seems to be holding back from easing policy for now. But that may change if a hard Brexit dents economic growth.5

Learn more

Explore the Economics collection

Subscribe to receive related content

Download the Deloitte Insights and Dow Jones app

Does central banks’ dovish stance point to low interest rates in the short-to-medium term? Most likely, yes. But there’s a catch—while low rates help consumption and investment, they may also cause higher debt accumulation, thereby extending pain for savers, pension funds, and insurers.

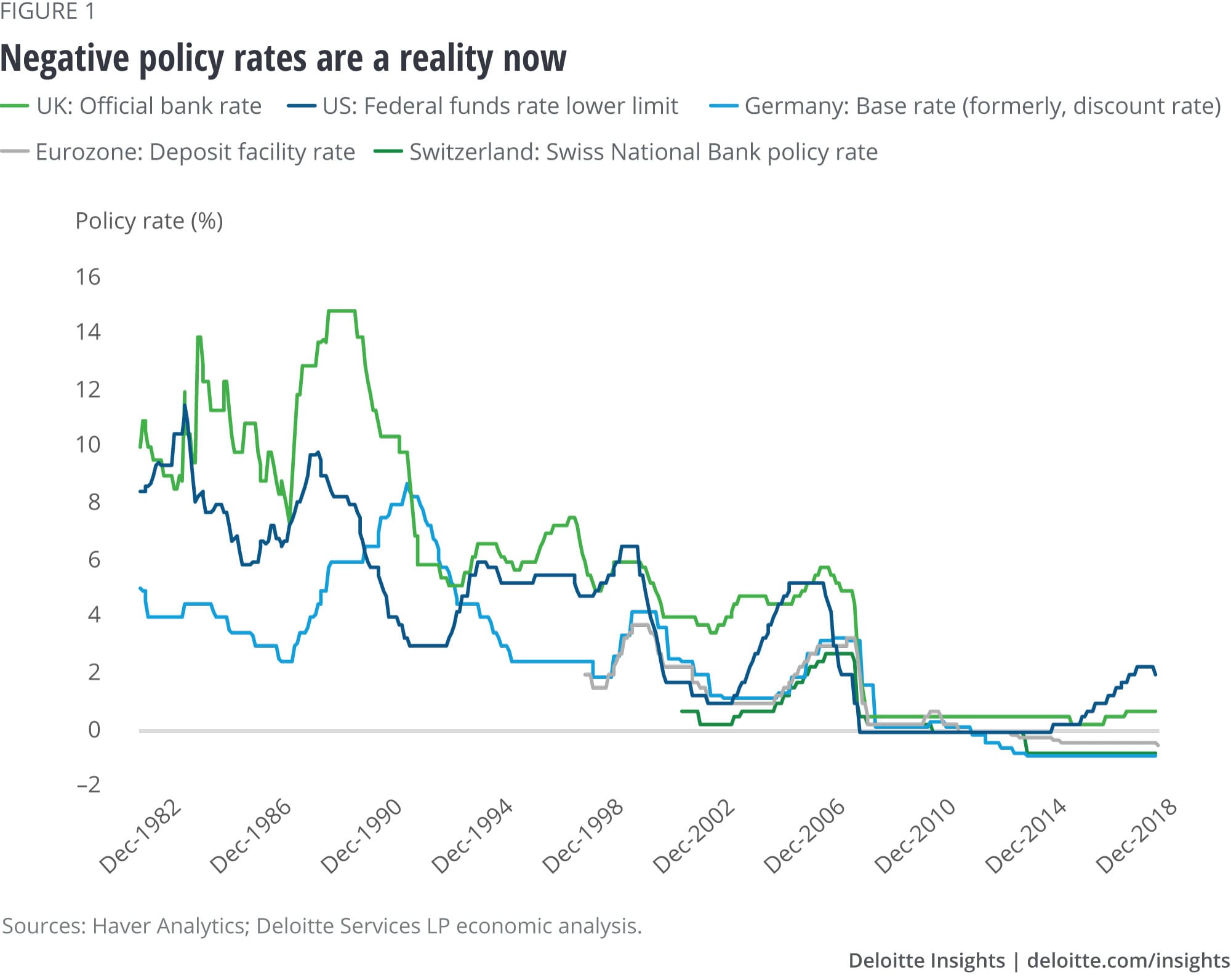

Low is where short- and long-term rates are now

While interest rates have been on a broad downward trend across developed economies for quite some time, this trend is more pronounced in the current economic recovery than in previous ones. In the United States, the lower limit of the federal funds rate has averaged 0.43 percent since July 2009, much lower than in the previous two recoveries—2.87 percent between December 2001 and November 2007, and 4.9 percent between April 1991 and March 2001.6 A similar trend is evident across key advanced economies, such as the eurozone and the United Kingdom (figure 1).

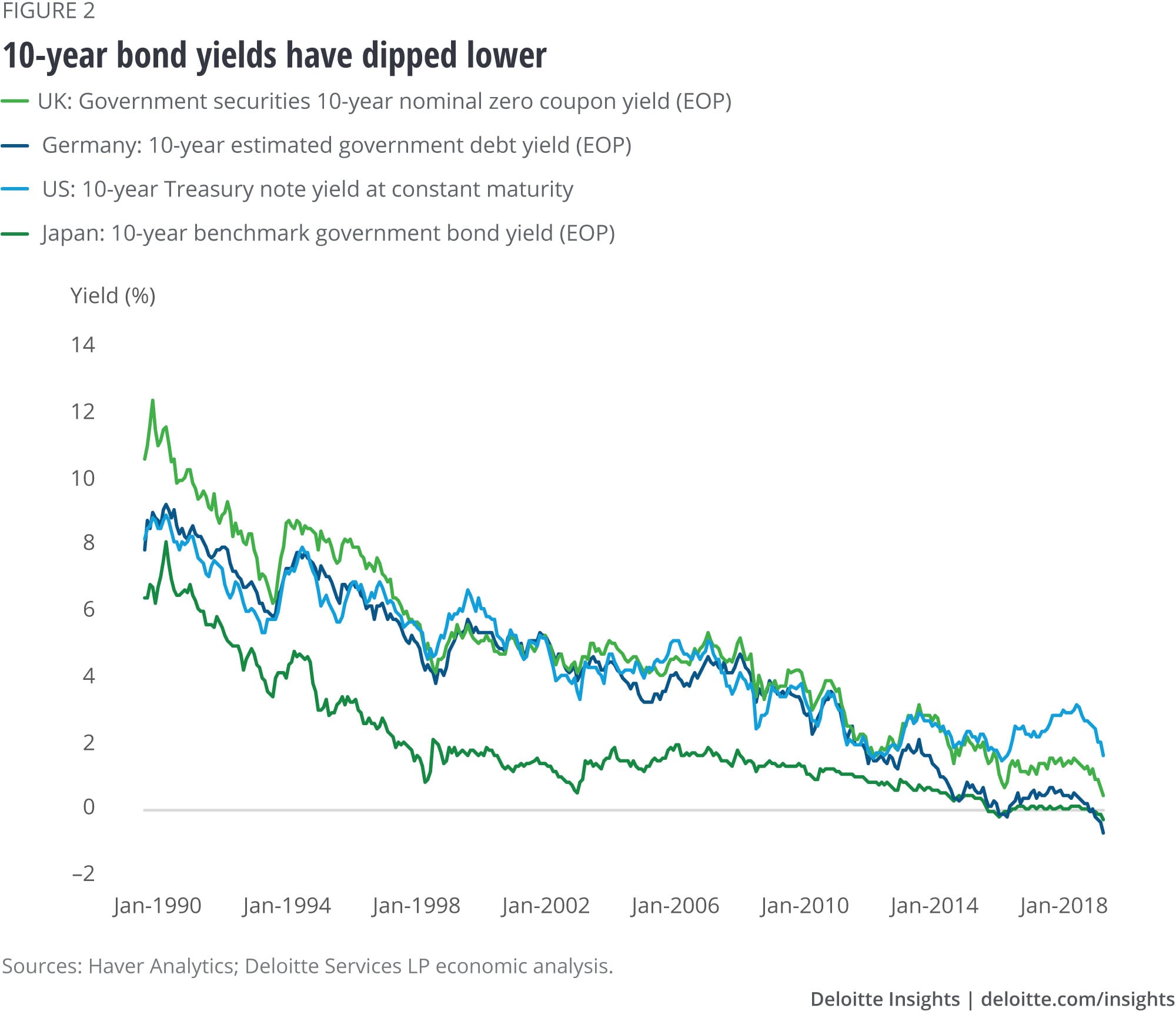

The broad decline is not restricted to official short-term rates alone. Long-term bond yields have also been falling over the years (figure 2). Yield on the 10-year US Treasury bonds, for example, has averaged 2.48 percent in the current recovery, compared to 4.44 percent in the preceding one and 6.35 percent in the one before.7 And negative yields for 10-year government bonds for Japan and Germany mean that instead of getting returns, investors are, in fact, paying money to hold on to government debt.

Savings rates too have been in decline. In the United States, the deposit rate on a minimum savings account of US$2,500 was 0.09 percent in August 2019, just a fraction of what it was in January 2000 (1.93 percent). During this period, the harmonized interest rate on new household deposits with maturity of less than a year in the eurozone fell to a meager 0.3 percent from 2.92 percent.

Low is where policy rates will likely remain for now

Policymakers in advanced economies are increasingly concerned about slowing economic growth. To make matters worse, inflation remains lower than target, and inflation expectations are subdued. Together, they are compelling reasons for policymakers to keep rates low.

Economic activity is likely to slow in 2019–2020

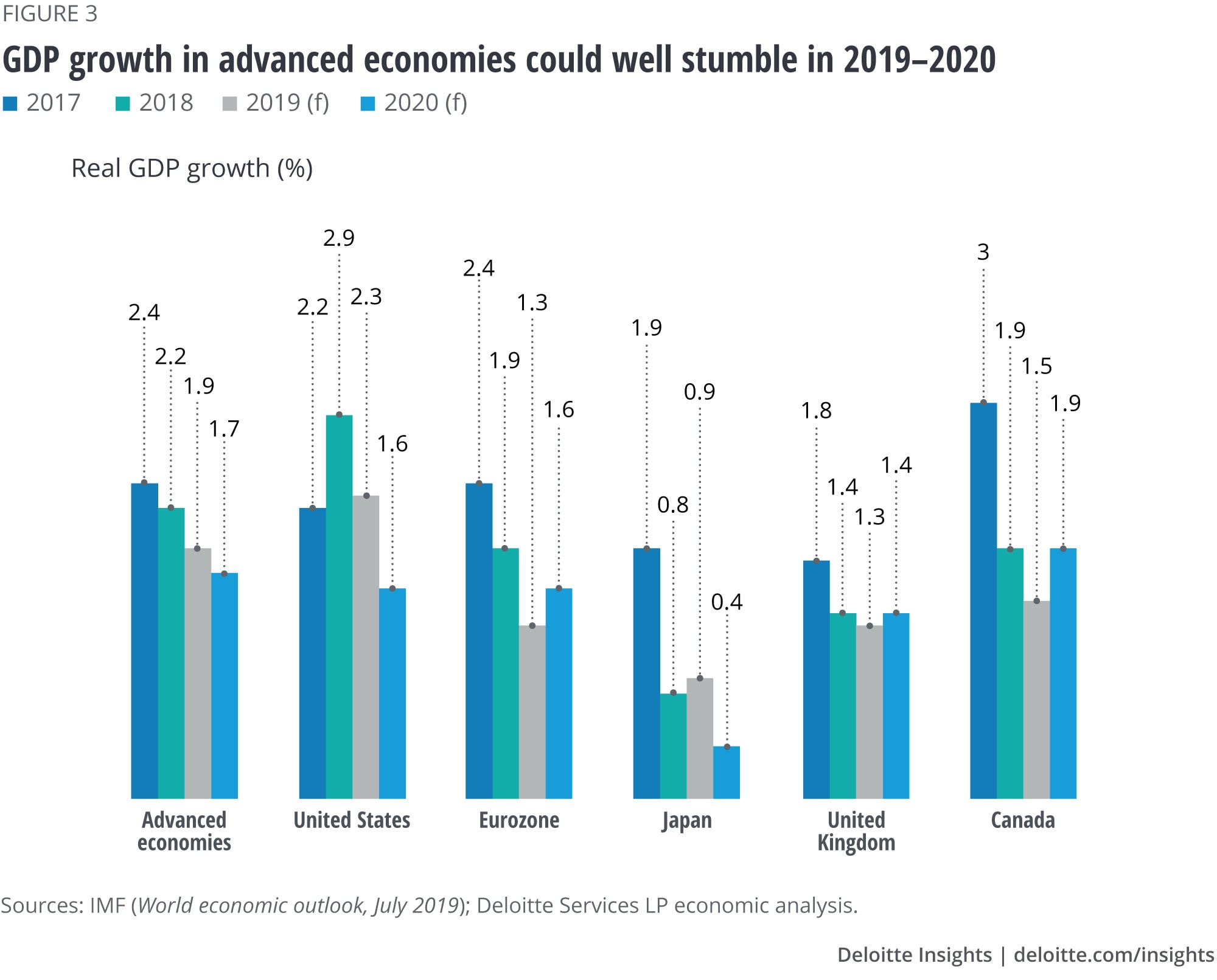

In the second quarter, economic growth slowed in the United States, the eurozone, Japan, and the United Kingdom, and the outlook for the next quarter isn’t much different. Deloitte economists expect US economic growth of 2.3 percent this year (down from 2.9 percent in 2018) and a much lower 1.6 percent next year. Additionally, they ascribe a 25 percent probability of a recession in 2019–2020.8 Concerns about the economic outlook were, therefore, a key factor in the Fed’s decision to depart from its rate hike stance and instead cut the federal funds rate in July and September.

In Germany, the eurozone’s largest economy, real GDP contracted in Q2, incoming data is weak, and there are fears of a contraction in Q3, which would mean a recession. Growth has also been subdued in other major economies in the region. Real GDP in France expanded by just 0.3 percent quarter-on-quarter in both Q1 and Q2 while in Italy, the economy barely grew in the second quarter. No wonder then that the ECB eased monetary policy further, wary perhaps that any delay in countering a slowdown will dent the region’s economy and hinder the recovery in countries such as Spain, Ireland, Portugal, and Greece that bore the brunt of the sovereign debt crisis.

Slowing economic activity in major advanced economies is not an anomaly; the global economy and world trade have slowed too. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) has warned that escalating tariffs between China and the United States could shave off as much as 0.8 percentage point from global growth in 2020.9 In its update in July, the Fund cut its forecast for global growth in 2019 and 2020. It now expects global growth to slow to 3.2 percent this year from 3.6 percent in 2018.10 Additionally, the Fund expects growth in advanced economies11 to slow to 1.9 percent in 2019 from 2.2 percent in 2018 and then further to 1.7 percent next year (figure 3). With an outlook as austere, it is unlikely that advanced economies’ central banks will move away from the path of loose monetary policy any time soon.

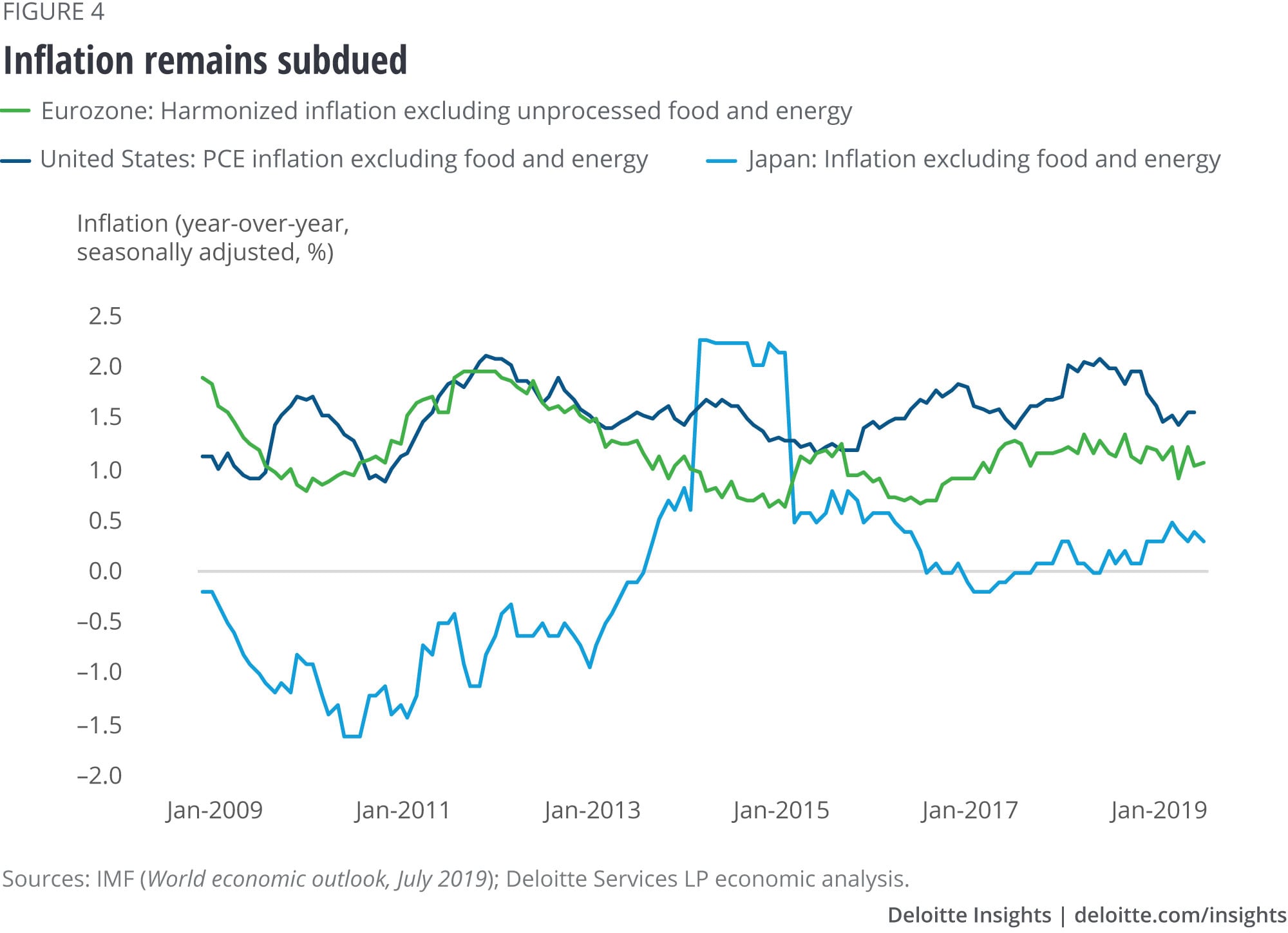

Inflation is a worry because it has not gone up enough

Despite years of low (and even negative) interest rates, inflation in advanced economies remains low and steadily below the target (figure 4). Japan perhaps stands out, with the central bank’s fight against deflation far short of desired results despite negative interest rates and years of quantitative easing. In July, for example, headline inflation was 0.5 percent, far lower than the BOJ’s 2.0 percent target (till 2021). Given that inflation has been below the target since the effects of a consumption tax hike in 2014 eased, it is unlikely that the BOJ would be reversing policy soon, especially with growth expected to remain subdued.12 A rising yen, primarily due to capital flows toward safe assets, is another of the bank’s concerns. With exports struggling given ongoing global trade tensions, the BOJ’s current policy favors a weaker yen, which is favorable for exports. It is a stance that the BOJ is unlikely to move away from in the next two years.

In the United States, core personal consumption expenditure inflation, the Fed’s preferred gauge for inflation, has rarely breached the 2.0 percent target since the start of the current recovery. Since December 2018, it has been on a downward trend. A quick look at 10-year bond yields, including Treasury Inflation-Protected Security yields, reveals that financial markets’ long-term inflation expectations remain lower than the Fed’s target. In the eurozone too, inflation has been edging down since the last quarter of 2018. As such, low inflation is strengthening central banks’ hand in easing policy further to stimulate growth.

A low interest rate scenario restricts monetary policy’s ability to counter a cyclical downturn. Between August 2007 and December 2008, the Fed cut the lower limit of its federal funds rate by a total of 525 bps. But now, the range available for rate cuts is much narrower. As for the ECB, with the deposit facility rate already at –0.5 percent and the main refinancing rate at zero, the room for maneuvering is even narrower. Asset purchases remain an option, but the ECB and the BOJ have already engaged aggressively, leaving the question of how much further they can stretch.

What comes after: Rising debt and worries for savers, insurance companies, and pension funds

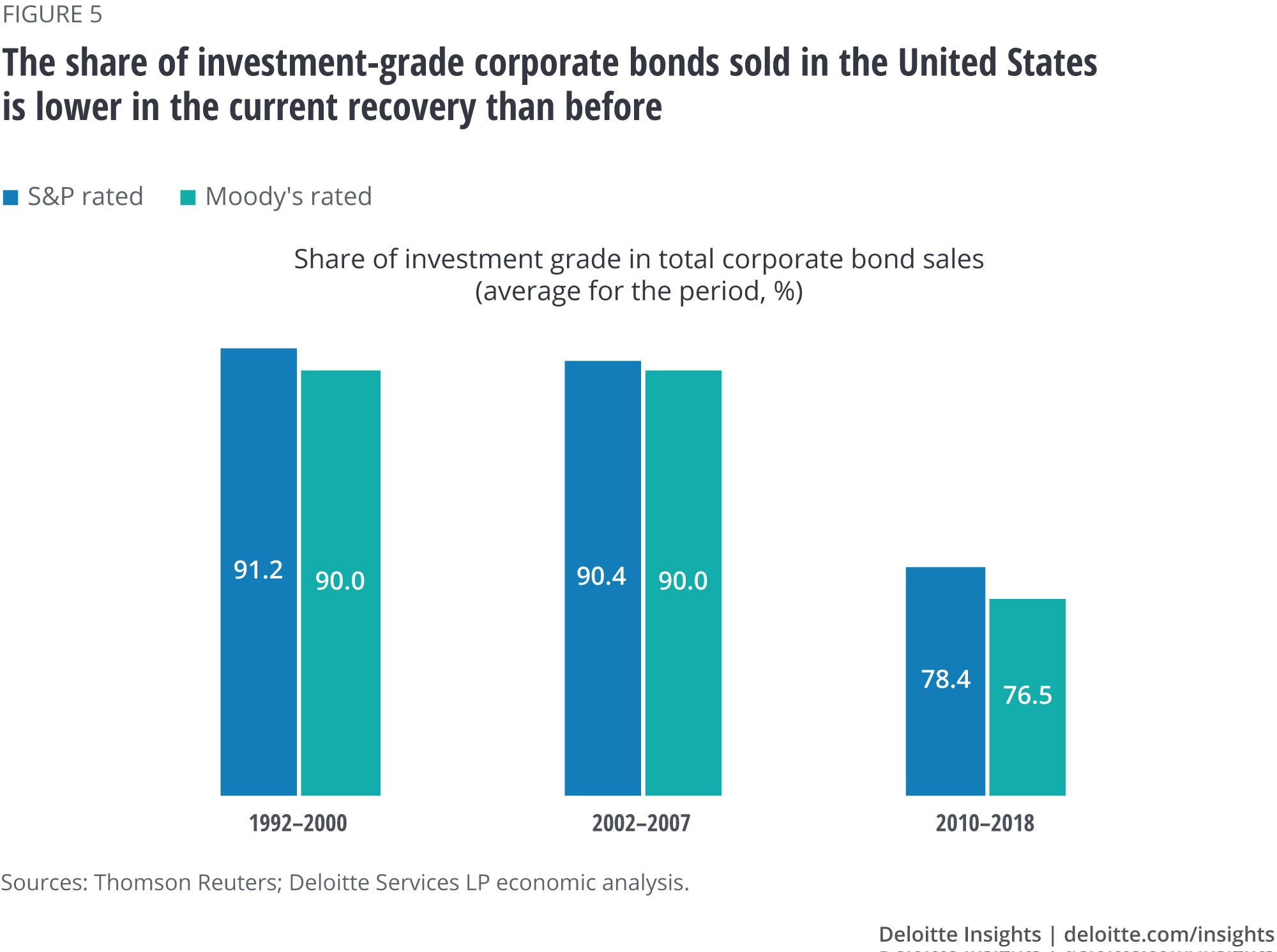

A prolonged period of low interest rates may lead to high leverage. This is of particular concern in the United States, where nonfinancial business sector debt was 73.8 percent of GDP in Q1 2019, the highest ever since the data series started in Q4 1947. Importantly, nonfinancial corporations accounted for 63.6 percent of this debt. While rising leverage is expected during an economic recovery as businesses invest and expand production, the quality of debt also matters. According to annual data from Standard and Poor’s (S&P) and Moody’s, the quality of debt issued in the United States during the current recovery is lower than in both previous ones.13 During the 1992–2000 recovery, an average of 91.2 percent of S&P-rated corporate bonds sold had an investment-grade rating; this share fell to 78.4 percent for 2010–2018.14 The same trend holds true for corporate bond sales with a Moody’s rating (figure 5). Furthermore, the percentage of corporate bonds sold with the lowest investment-grade rating, for both S&P- and Moody’s-rated bonds, has been higher during this recovery compared to the two previous ones. This shows that, even among the investment-grade bonds sold during the current recovery, the share of bonds that are most susceptible to a credit downgrade to junk has gone up.

The decline in the share of investment-grade bond issuances has come at a time of rising leveraged loans—bank loans to firms with high debt levels and high debt service costs due to relatively poor credit quality. According to a recent study by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the size of the leveraged loan market in the United States and Europe has more than doubled since 2010 to about US$1.4 trillion outstanding.15 Perhaps a bit more worrying is the trend in securitization of leveraged loans during this period. The same BIS study mentions that more than 50 percent of this figure is securitized through collateral loan obligations (CLOs). The rise in CLOs during this recovery—akin to what it was for securitization of subprime mortgages in the years leading to the Great Recession—raises the risks for banks and other nonbanking investors in CLOs, such as insurance companies.

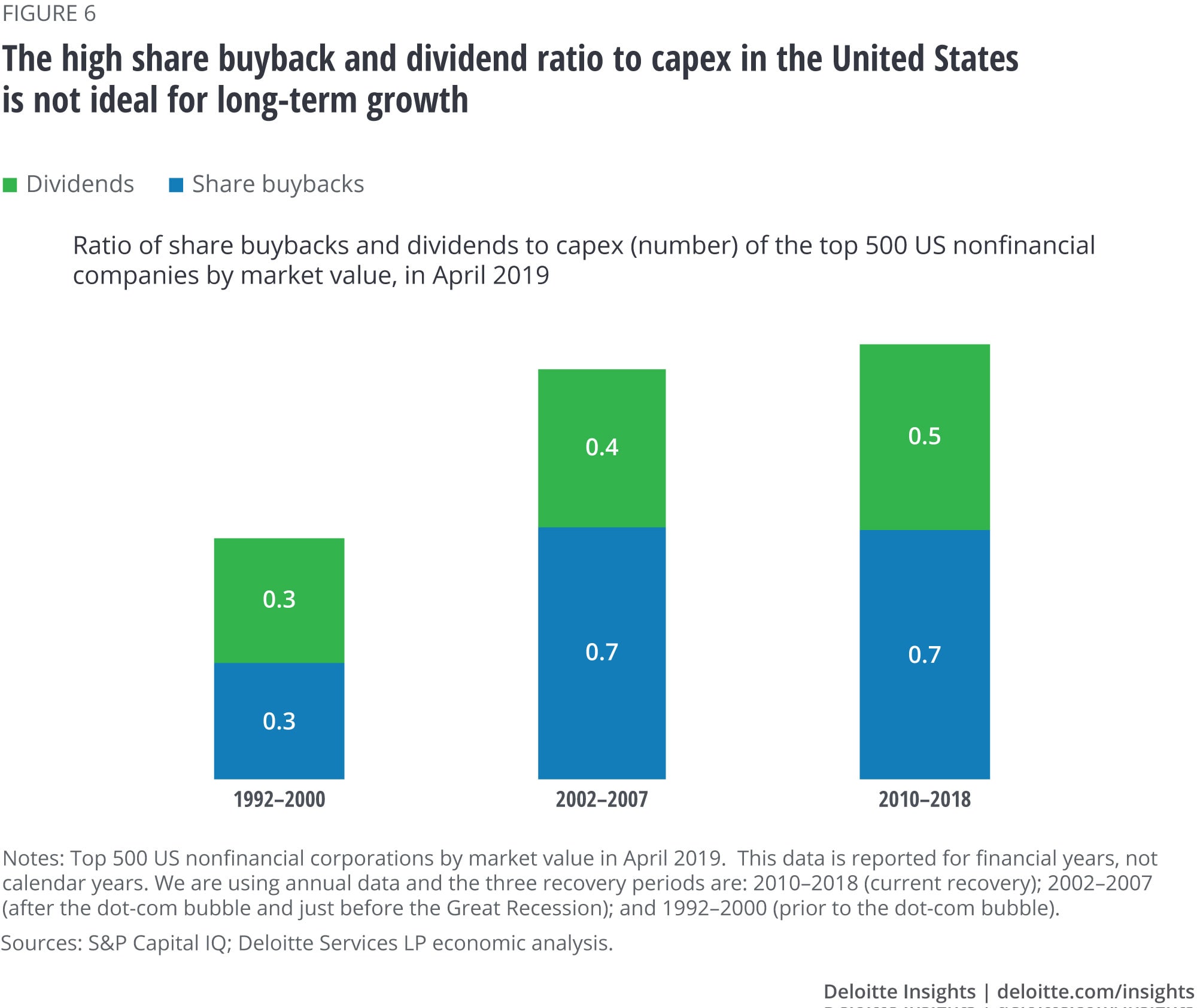

Often a rise in debt is accompanied by a surge in investments, which is good for long-term economic growth. In the current recovery, however, investment growth has not been as much as previous ones. For example, data from S&P Capital IQ for the United States reveals that share buybacks and dividends have exceeded capital expenditure in the current recovery (figure 6).16

Prolonged low interest rates are also not good news for savers either. In Japan, ordinary bank deposit rates averaged about 0.2 percent in 2007. And if that seems a bit low, here’s more food for thought—the rate fell to 0.001 percent in October 2016 and has been at that level since then. Pensioners and those nearing retirement age suffer especially as they typically hold more of fixed-income assets (such as bonds) in their portfolio than younger people who typically invest more in equities.17 If yields remain low, people may end up working longer due to higher retirement age, pay more taxes, and yet earn lower incomes in their old age.

Insurance companies and pension funds face the risk of falling short of their liabilities if interest rates remain low for long. In the United States, the yield on 30-year Treasury bonds has been steadily declining: It was 1.96 percent at the end of August, 3.0 percent at the end of 2018, and 4.5 percent right before the onset of the Great Recession. In the eurozone and Japan, yields have turned negative for some long-term bonds. With their bond portfolio not yielding enough returns, insurance companies and pension funds may move toward riskier assets in search of higher yield.18 Another study by the BIS revealed that in a scenario of prolonged low interest rates, insurance companies and pension funds faced higher solvency risks than banks.19

Is it time for fiscal policy to take over?

With limited options available to central banks, one could look at fiscal measures to take on a larger countercyclical role. But is there enough fiscal space left? In the eurozone, Germany may have enough room for fiscal stimulus, but with the wider region still picking up the pieces after the sovereign debt crisis, any regionwide fiscal response will likely be limited. In the United States and Japan, high government debt levels limit the ability of a fiscal response as seen during the Great Recession. This is where low interest rates may be helpful—the cost of borrowing will be low for governments. Governments can use these funds to boost the economy through spending on assets, such as infrastructure. This is something that Keynesians will likely approve of.

Explore the Economics collection

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article5 years ago

-

Retirees of the future Article5 years ago

-

United States Economic Forecast Q3 2024 Article1 month ago

-

Brazil economic outlook, August 2024 Article2 months ago

-

Is the yield curve a modern-day Chicken Little? Article5 years ago

-

What are the long-term dangers of the US budget deficit? Article5 years ago