What are the long-term dangers of the US budget deficit? Economics Spotlight, May 2019

6 minute read

24 May 2019

US debt has increased substantially over the years. While many believe it's not a cause for concern, it may be prudent to stem the increasing budget deficit before it impacts the US economy and the global financial system.

If something can’t go on forever, it will stop. (Stein’s Law)

Merle Travis once sang that the coal miner was “another day older and deeper in debt.”1 Today, that’s a pretty good description of the federal government. For now, US government debt remains popular among global investors. That’s a good thing, because the US government is issuing a lot of it. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects a 2019 federal deficit of about US$900 billion.2 That’s US$900 billion worth of new treasuries the US government will have to sell. And the CBO expects that number to grow over the next 10 years.

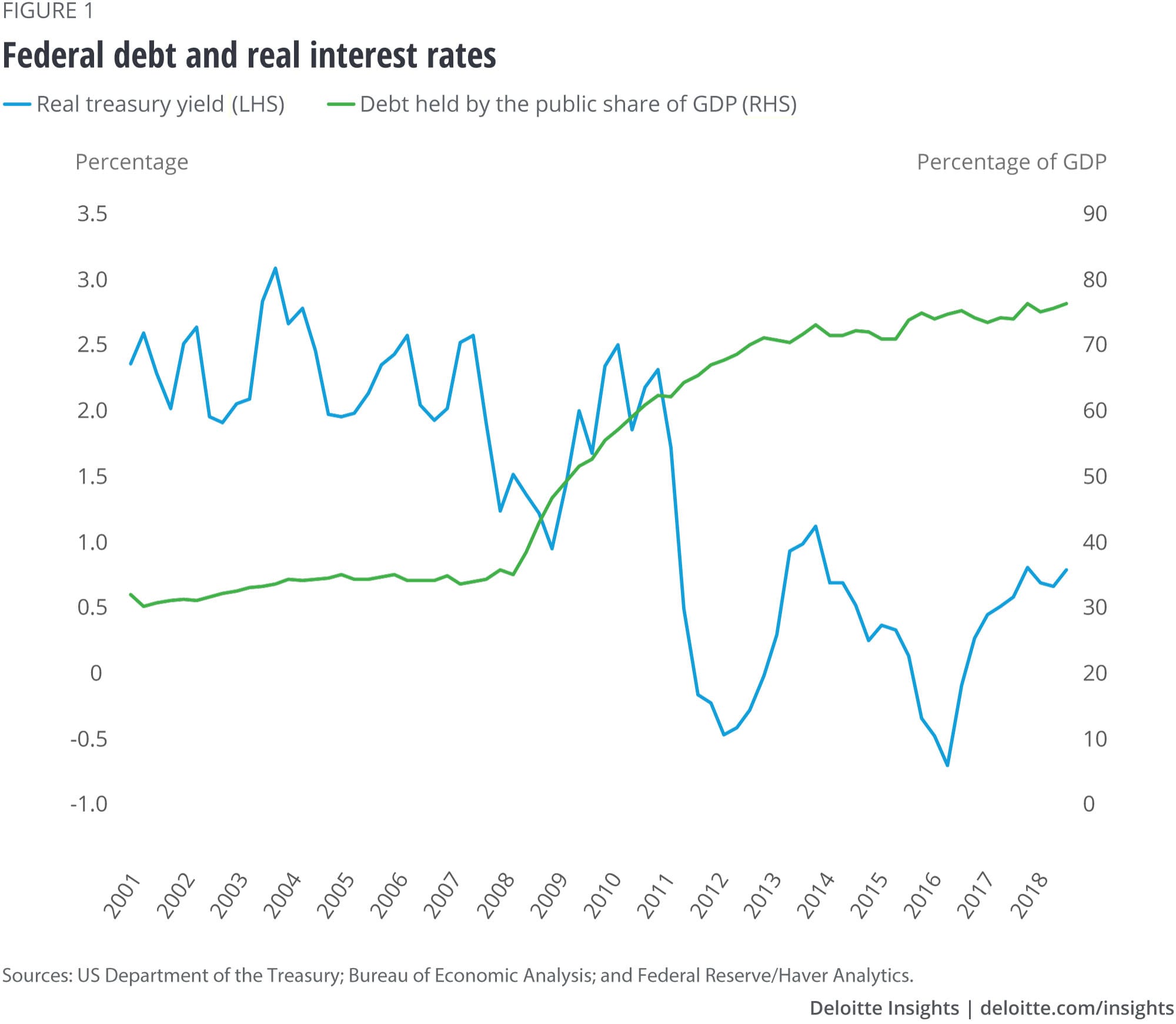

It sounds like a substantial amount of money—and it is. But markets don’t seem to mind. Figure 1 shows the supply of federal debt against the real 10-year treasury yield. From 2008 to 2014, debt held by the public rose from about 35 percent of GDP to over 70 percent of GDP. Yet the real long-term interest rate fell below 1 percent. It even turned negative on two occasions.

While the growth of government debt, which slowed after the two-year stimulus package passed at the beginning of the Obama administration to help the economy out of recession, ran its course, the Trump administration’s tax cuts and increased government spending have the debt on track, expected to reach 93 percent of GDP by 2029. But investors don’t seem bothered.

It wasn’t so long ago that many economists were warning that the United States was on an unsustainable course, borrowing too much, and that a crisis would eventually occur. What happened?

The shrinking definition of safe assets

Investors—especially banks—need safe assets. Such assets are a key part of any portfolio, and, for banks, often a legal requirement. But the Great Recession showed that some supposedly “safe” assets were not so safe. AAA-rated mortgage-backed securities (MBS) defaulted, and even some government debt came to be seen as relatively risky. By one estimate, the global supply of safe assets fell from US$20.5 trillion in 2007 to US$12.3 trillion in 2011.3 Among assets markets no longer seen as safe were Italian and Spanish government debt, and various types of private and US government MBS.

It’s not surprising, then, that the smaller supply of safe assets would drive up the price of those assets. And by 2011, more than 80 percent of the outstanding stock of safe assets were US treasuries.4 Hence the decline in treasury yield, reflecting this jump in demand.

That’s taken the US government’s debt out of the headlines. Recent economic policy and policy proposals now tend to downplay or ignore the impact on government debt. From former House Speaker Paul Ryan5 to new House member Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, many leaders have downplayed the importance of the deficit for policymaking. Other priorities—from tax cuts to the Green New Deal—seem more important to them.

No worries?

While the US government debt is no longer a key political issue, economists continue to debate whether the country should be paying attention to the problem. There are three main schools of thought about the issue—two “no worries” and one “maybe we should worry.”

The politicians are correct, and deficits don’t matter.

Some policymakers may simply prefer to ignore the long-term impacts of piling up debt because they won’t be around to deal with the consequences. But some economists have made a serious argument that debt levels don’t matter. Much of this thinking is collected under the title of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), and is associated with liberal economists. But some Wall Street economists have embraced the idea as well.

In simple terms, proponents of MMT argue that since the US government can always create money to repay loans, there is no real constraint on borrowing. Government borrowing can only be too large if it raises aggregate demand to inflationary levels. In the absence of inflation (certainly true today), there should be no concern about the size of government borrowing.6

MMT very much remains a minority opinion among economists. But it’s popular among politicians because it seems to promise the removal of an important constraint on policymaking—the rise in the budget deficit. Proponents of the idea may argue that this misrepresents their purpose, but to little avail—the possibility of a free lunch is always alluring.

There are limits to government borrowing, but we are very far from those limits. It’s not, therefore, an urgent problem.

A larger group of economists argue that the deficit is a potential matter of concern, but that under current conditions, it is not a priority. These analysts note that “crowding out”—the replacement of private borrowing and investment by public spending—is not likely to be a problem when interest rates have remained very low. So, while there are indeed constraints on the budget, those constraints are practically not a problem for current policymaking. And it would be a mistake to cut otherwise useful government programs to constrain the growth of the deficit in the near term.7

The continuing accumulation of government debt remains a problem—even if nobody wants to discuss it. And the longer we wait to attack the problem, the more difficult it will be to solve.

Although it’s not very popular among policymakers, many economists continue to argue that the US economic policy should focus on reducing the deficit and limiting the growth of debt (or even reducing the outstanding debt). This is, of course, the logic of traditional economic analysis. All mainstream schools of contemporary macroeconomics have long treated excessive government debt as a potential problem.8

Why does it matter?

The group of economists who believe there is cause for worry believe that the growing debt could lead to two problems for the US economy.

First, there is evidence the government borrowing will eventually raise interest rates and reduce private investment spending.9 Running large deficits when the economy is already in full employment will simply move economic activity from the private sector to the public sector, at the expense of long-run growth.

Second, although it may be hard to believe, at some point global investors may begin to question the ability of the United States to repay its obligations. A few years ago, some analysts suggested that a debt-to-GDP ratio of around 90 percent was a “red line,” with the possibility of a crisis—and likely significantly slower growth—waiting for countries that issued so much debt. This followed from Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart’s research on financial crises.10 A closer examination of specific countries suggested that this rule of thumb was unreliable. Japan, for example, has avoided a crisis despite having run a debt-to-GDP ratio of over 200 percent for the past 10 years. The United States has some advantages compared to most countries. The US government has an enviable history of reliability, having never defaulted since Alexander Hamilton managed to convince the first Congress to repay state and confederation debt from American Revolution.11 And US debt’s role in the global financial system provides the country with what the French in the 1960s called an “exorbitant privilege”—a ready demand for US assets that are used for other purposes (and especially as safe assets in countries that don’t have large, liquid, or trustworthy domestic bond markets).

The danger is that those advantages could eventually erode. If the debt grows large enough, global investors will become concerned about the ability of the US government to repay the assets. That may take decades. It might not even happen. Nobody knows how large the US debt could grow before it becomes a problem. But the risk is there, and the damage to the US economy could be substantial. Assuming the deficit doesn’t matter means taking a rather large risk with the US economy—and with the global financial system. It’s probably a good idea to think carefully before taking that risk.

Explore the Economics collection

-

Rising corporate debt: Should we worry? Article5 years ago

-

Will political tensions derail economic gains in Asia Pacific? Article5 years ago

-

Consumers in advanced economies: A tussle between tailwinds and headwinds Article6 years ago

-

Volatility in emerging economies: Is contagion too harsh a word? Article6 years ago

-

How the financial crisis reshaped the world’s workforce Article5 years ago

-

All in a day’s work—and sleep and play: How Americans spend their 24 hours Article6 years ago