Using virtual health to push equity in health care has been saved

Perspectives

Using virtual health to push equity in health care

Meeting the equity imperative in virtual health care through intentional design and deployment

Over the past decade, sectors across the health care industry have invested considerably in virtual and digital health. The area is poised for tremendous growth, as COVID-19 accelerated adoption and incubated vast opportunities for virtual health to improve access to services while delivering safe and convenient care.

Explore content

- What is health equity?

- Digital health equity as an imperative: Why equity drives value

- Designing a more equitable future: Smart first steps

- What is virtual health?

- Get in touch

What is health equity?

Health equity is the fair and just opportunity for every individual to achieve their full potential in all aspects of health and well-being. Today, the United States faces significant health disparities across many dimensions that are evidence of systemic structural inequities affecting both individual and community health and well-being (these inequities are explored in further detail below). These disparities are also reflected in virtual health care; however, this moment in the industry also presents an enormous opportunity to drive change for the better and unlock value while doing so.

If virtual health programs are designed intentionally with equity as a guiding principle, virtual health could improve access, continuity of care, and care management. These shifts could transform care delivery to be more convenient, accessible, and efficient—ultimately leading to improved outcomes. Beyond the social benefits of improving care, prioritizing equity in virtual health would also help health care organizations achieve a competitive advantage and unlock value by enabling personalized care for expanded customer segments.

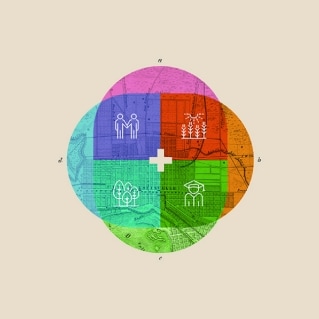

To activate this equitable future, organizations should begin by understanding the three main arenas of virtual health inequity: 1) infrastructure and access, 2) digital engagement and cultural competency, and 3) technology development and analytics.

What is virtual health?

At-a-distance interactions that are leveraged to further the care, health, and well-being of consumers in a connected, coordinated manner. To be considered virtual health, all communications and information transfers must occur through nonphysical means either synchronously or asynchronously. Virtual health is unique, as it encompasses engagement across the overall health journey beyond just the act of care, and includes the entire ecosystem of prospective and current consumers including their caregivers, families, providers, employers, and producers.

Digital health equity as an imperative: Why equity drives value

Market, regulatory, and moral incentives for prioritizing equity in virtual health are beginning to align. COVID-19 dramatically accelerated the adoption and reimbursement of virtual health, particularly among Medicare and Medicaid populations. These populations are very different in terms of race, income, and age than those covered under private insurance. The vast rural, elderly, low-income, and racially and ethnically diverse populations covered under Medicare and Medicaid have historically faced disparities in access to not only virtual health but the health care industry at large. These shifts in coverage—combined with expanded internet access among rural, lower-income, and racially and ethnically diverse communities due to investments in broadband infrastructure and 5G—mean the virtual health industry needs to be ready to serve new and more diverse customer segments. Prioritizing equity in the design and delivery of virtual health will allow organizations across the industry to meet these segments’ needs and reap tremendous benefits.

As health care leaders look to design equitable virtual health programs, they will need to better understand the three arenas where virtual health inequities play out and how to address those inequities: (I) infrastructure and access, (II) digital engagement and cultural competence, and (III) technology development and analytics.

Virtual health solutions must be designed and deployed with careful consideration of differing levels of broadband access and availability of technology, as well as mindfulness of appropriate environments for virtual care. Twenty-five million Americans cannot access the internet at home. Lower levels of access especially affect older Americans, Medicaid members, and those with lower incomes. In 19 states, households with a Medicaid enrollee were 10% less likely to have internet access than households without an enrollee.

Adults living in households with an annual income of less than $30,000 per year are far less likely to report using the internet than households with incomes of more than $75,000. Additionally, according to the Pew Research Center, 27% of US adults aged 65 and older reported they did not use the internet in 2019. Beyond internet access, Americans with lower levels of education, lower income levels, and who live in rural areas report lower rates of smartphone ownership. This may mean not all populations benefit equally from the rise of 5G connections, despite the technology’s enormous potential to connect the 46 million rural Americans and 13.6 million urban households without internet access.

Paths to equity:

• Partner with local resources: Work with schools, shelters, libraries, community health centers, and more to set up “Connectivity Zones” where those without reliable internet service at home can go to receive needed virtual care.

• Fund or provide technology directly: Devote resources to bringing virtual health equipment and/or reliable Wi-Fi to patients or members who need it. Such investments may transform how individuals successfully manage chronic conditions from home.

• Offer technical and culturally competent support: Extend care team composition or capabilities to assist in the setup and use of technology, and ensure staff is culturally competent. Such support can enable effective remote patient monitoring and hospital at-home services.

Populations leveraging virtual health solutions have varied levels of digital and health literacy, cultural and language barriers, accessibility needs, and self-advocacy and care team advocacy.

Lack of digital literacy, whether it stems from preference or lack of internet access, can impede the ability to find and use virtual care. Populations with lower digital literacy in the United States tend to be less educated and older, and are more likely to be Black, Hispanic, or born outside the United States. Furthermore, studies have shown that older, lower-income, and less educated populations access health information online less frequently or are less interested in online provider interaction compared to counterparts. These disparities may help explain why some studies have shown these same demographic groups having lower levels of telehealth usage or reporting lower comfort levels of telehealth utilization compared to counterparts.

Paths to equity:

• Tailor intuitive and accessible user experiences: Use simple language, straightforward design, and simplified navigation when designing apps and web pages—and be sure to design for all kinds of modalities and devices, from laptops to tablets to cell phones.

• Conduct targeted outreach: Reach out to segments of the patient population that are less digitally literate to provide assistance and education.

Provide accessible educational materials: Publish step-by-step instructional documents, visual workflows, and video tutorials that can help patients and staff smoothly navigate virtual encounters and educate consumers on online privacy and security.

• Sponsor or launch localized virtual health hubs: Connect patients to physical sites with the technological and staffing resources to assist with virtual visits.

• Leverage existing social supports: Use technology to seamlessly engage and connect social supports (e.g., family members, friends, libraries, and community organizations) in integrated platforms.

As we have noted previously, biases in health care advanced analytics are a serious barrier to a more equitable future. Bias can increase mistreatment, undertreatment, and overtreatment—just one recent example of this phenomenon includes a biased algorithm inappropriately assigning Black women lower chances of successful vaginal birth after caesarean section.

These issues, in turn, can lead to poor health outcomes for consumers and worsened financial performance for hospitals, health systems, health plans, health technology firms, and life sciences companies. Consumer sentiment acknowledges such dangers—57% of consumers believe artificial intelligence has the potential to do damage over the next 10 years due to misuse. Organizations can avoid these outcomes by building processes and procedures (as described below) to spot and combat biases before they infect their use of analytics technology.

Paths to equity:

• Demand robust governance: Establish data guidelines and thresholds and encourage teams to check each other’s assumptions and models for quality and sensitivity. Use robust governance to protect sensitive consumer data, and retrain virtual health technologies (e.g., virtual triage systems) that are discovered to be biased. Demand transparency and explainable information when collecting data sets and training models. Reference Deloitte’s Trustworthy AI framework to accelerate your understanding.

Build diverse teams: Design (or redesign) the organization’s operating model/structure to focus on team diversity. Train data scientists and developers to avoid common technology bias pitfalls within virtual health. In the absence of diverse teams, organizations that are intentional about activating equity can still risk perpetuating bias.

• Apply human-centered design: Leverage human-centered design and testing for accessibility and usability in virtual health applications and programs to help ensure equitable deployment across relevant populations. Involve multiple stakeholders—especially historically underrepresented patient populations—in advanced analytics design.

• Audit proactively: Engage subject-matter experts and tools to audit advanced analytics and underlying data sets used in virtual health programs. Commit to a regular cadence of external audits to detect bias and define mitigation tactics when the tool or model is launched. Recurring audits can help account for changes to consumer behaviors and as the algorithm matures.

Designing a more equitable future: Smart first steps

Equity must be embedded into all aspects of virtual health solution design, development, and deployment, especially within organizations’ high-level priorities and strategic initiatives. This process should be intentional and human-centered (focused on impact to consumers), as we recently outlined in our virtual health care experience white paper. To activate equity, leaders should:

- Adopt inclusive and diverse human-centered design (HCD) practices for technology development to ensure solutions consider underlying drivers of health, account for diverse needs, serve all populations equitably, and do not perpetuate biases (reference Deloitte’s Experience-led virtual health paper for more detail on HCD for virtual health).

- Prioritize diversity and equity in the care model design, workforce training, communications strategies, and deployment of virtual health solutions.

- Adopt phased implementations that “move at the speed of trust” to drive equitable adoption of virtual health technologies and services.

- Establish policies, regulations, and standards to balance protecting consumers, driving equity, and encouraging innovation in virtual health.

- Conduct ongoing monitoring of key equity metrics to understand if and how solutions, analytics, and practices impact equity.

As the United States continues to grapple with the disparities laid bare by the pandemic and the staying power of virtual health becomes more and more evident, it’s critical that the health care industry intentionally designs virtual health programs and solutions with equity as a guiding principle.

Recommendations

Virtual health accelerated

The COVID-19 pandemic led to an accelerated adoption of virtual health. But will that momentum continue to build? Here’s how health systems could use the growing acceptance of virtual health to transform delivery models.

Activating health equity

Life sciences and health care organizations have a central role in advancing equity in the pursuit of health and well-being for all.