Solving the succession paradox has been saved

Perspectives

Solving the succession paradox

CFO Insights

In this issue of CFO Insights, we will discuss why succession planning can be an effective part of an organization’s growth strategy and a signature feature of their corporate culture.

Explore content

- Introduction

- Why succession planning matters—and why it is hard

- Achieving a centered approach

- Toward a centered approach

- Balancing empathy, objectivity, and discipline

Introduction

While organizations realize that succession planning is an important priority, few manage to execute it well. In fact, a 2014 Deloitte study showed real market frustration with succession planning efforts: While 86 percent of leaders saw leadership succession planning as an “urgent” or “important” priority, only 13 percent believed they did it well.1

The problem? A more recent research effort concluded that most companies doing succession planning are often derailed by a host of symptoms that point back to a common culprit—the failure to recognize and address the impact of human behavior on the succession planning process.2 Few organizations seem to combine a disciplined, data-driven process with a user-friendly, people-centric approach that adequately engages stakeholders. More often than not, companies either avoid succession planning altogether or take a dispassionate, process-oriented approach that minimizes, or even ignores, the very real impact it has on the people involved.

The results of that research suggest that succession planning is most effective when it takes a “centered” approach that focuses on people first while maintaining objectivity and procedural discipline.

Why succession planning matters—and why it is hard

The potential gains from handling succession planning well go far beyond the obvious result of having a steady pipeline of leaders ready to step into new roles. Additional benefits cited by interviewees include a more diverse portfolio of leaders, higher-quality decisions around promotions and developmental investments, enhanced career development opportunities for emerging leaders, a stronger organizational culture, a "future-proofed" workforce, and greater organizational stability and resilience.

However, many participants were also quick to give reasons why they weren’t seeing the expected value (see "Where succession planning falls short," page 4). For example, succession planning, by its very nature, takes years to bear fruit, while leaders are typically rewarded based largely on short-term accomplishments. At the same time, the process can be destabilizing. Organizations may minimize their importance because they don’t want the process to be perceived as a lack of confidence in current executives. Similarly, executives may be hesitant to raise the idea of succession planning, lest it is perceived as signaling their future intentions.

Within finance, there can be advantages and disadvantages when it comes to succession planning for the CFO. On the plus side, the analytical nature of the function may make it more likely that leaders will be comfortable using data to inform their decisions about successors. At the same time, however, the rapid evolution of the CFO’s role—and the relentless pace of change in the digital era—can mean CFOs are perpetually playing catch-up and, thus, are less likely to address long-term planning needs.

Still, succession planning can be a critical differentiator between a good CFO—and a great one (see "Journey to CFO: Lessons for the next generation," CFO Insights, July 2018). CEOs and boards expect their CFOs to have a deep bench of talent prepared to step into any leadership gap—an asset critical to the entire enterprise, not just the finance organization. Given the larger trends at play, however, their expectations of what’s needed on that bench have broadened. Instead of just fundamental technical skills, future finance leaders are expected to drive change, exert influence without using numbers, nurture talent, and serve as strategic advisors to other parts of the organization. And it is up to the CFO investing in that talent to both pinpoint and distinguish between leadership attributes (meaning innate qualities such as self-confidence, conceptual thinking, emotional intelligence, willingness to experiment, etc.) and leadership capabilities (meaning skills that can be learned such as influence, business judgment, execution, building talent, etc.)—and project what balance of traits will be needed several years into the future.

Achieving a centered approach

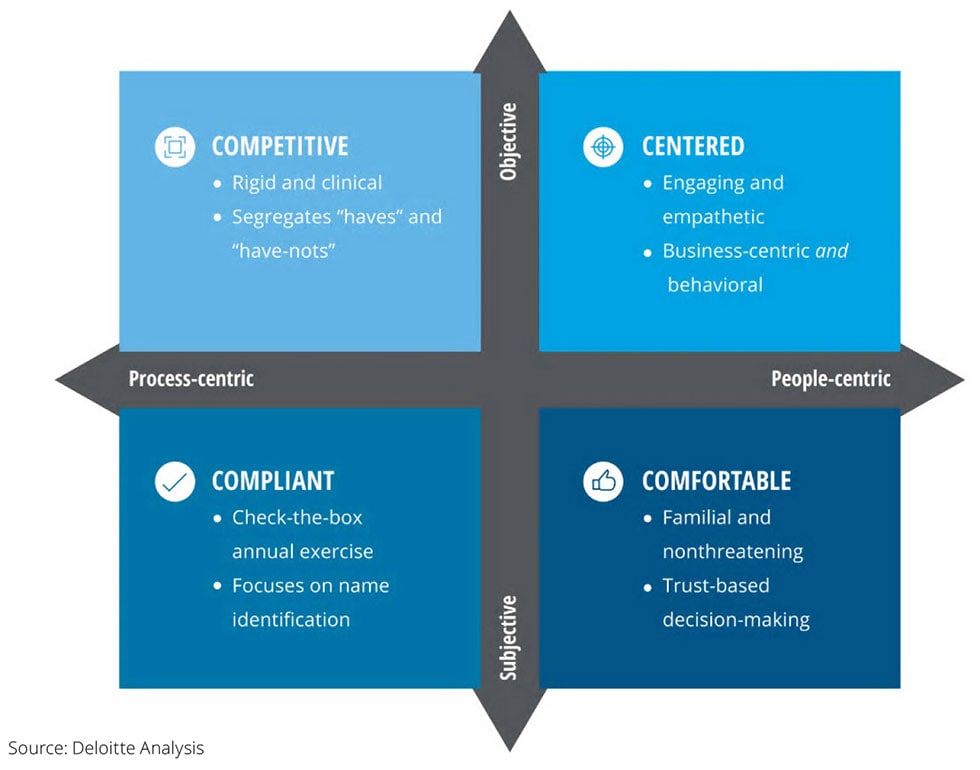

Current approaches to succession planning can be classified into four types (Figure 1). Three reflect how most surveyed organizations currently operate, and one represents what the research suggests is most likely to make succession planning a strong lever for growth.

- Comfortable. Organizations using an informal, intuition-driven approach to succession planning leave these decisions to a small group of leaders who tend to select successors based less on objective data than on reputation and tenure. This approach is often found at founder-based, private companies that continue to conduct business in an old “family business” style regardless of their size. While it helps maintain the old culture, it is fraught with bias and can lead to complacency and stagnation.

- Compliant. Many other organizations recognize the importance of standardized processes, objective data, and a regular cadence of activities to structure their succession planning decisions. But with more immediate priorities competing for leaders’ time, these tools and processes can fall by the wayside, allowing subjective decision-making to take over. This can be particularly evident at organizations where the onus for succession planning rests explicitly with the human resources (HR) function.

- Competitive. This style is characteristic of organizations that take succession planning seriously and build objective processes to evaluate and advance chosen successors. While this approach may be effective at identifying and promoting future leaders, it typically ignores the very real human reactions that can arise. The process can be perceived as a cold and threatening corporate program being done to individuals, and not for them. As a result, many participants tend to look for ways to “beat the system” or question the validity of diagnostics in order to raise their own stock or that of the candidates they support.

- Centered. Finally, a “centered” approach is designed to put the people involved—both the leaders managing the process and the successors being considered—at the center and is supported by processes that help decision makers maintain objectivity. Recognizing that succession planning has a huge impact on the careers of the current leaders who are responsible for its success, and acknowledging the emotions involved for both current and prospective leaders, this approach focuses on creating an environment that channels emotions productively. It uses people-centered design tools that allow organizations to consider objective talent assessment criteria without causing the leader community to feel threatened by the process. The aim is to create a succession program that leaders want to participate in, which can only happen when all participants appreciate its value and feel that it is fair and easy to navigate and believe it ultimately creates more opportunities for all involved.

Figure 1: Four approaches to succession planning

Toward a centered approach

Five key practices can help organizations move their succession planning efforts toward the centered state.

- Make it worthwhile

Asking leaders to fully engage in succession planning without an emphasis on their own interests is likely to result in apathy and avoidance. Organizations can manage these issues by offering bigger, bolder opportunities to incumbents so that they will focus on succession. Many leading organizations craft short- and long-term incentives that reward leaders for creating environments that develop successors, not just identify them. - Establish accountability and advocacy

Who is responsible for identifying and developing top talent—the CEO, CFO, CHRO, direct managers, or the board of directors? Research shows that, while people may acknowledge the importance of an activity, they won’t engage in it until clear accountability has been assigned.3 Interestingly, it doesn’t much matter who specifically has organizational accountability for succession planning—as long as it’s clear where the accountability lies. Having one or more senior-level advocates for succession planning is also crucial in building an effective succession culture. - Focus on the future

At its core, succession planning is about preparing an organization for the future, yet many organizations build their succession processes around the needs of current roles. Within finance, one smart move can be to help promising young professionals to gain exposure to other business functions within the organization as well as to the latest trends in the broader business world. That may mean stretch assignments, temporary job rotations, or exposure through a reverse mentoring program (something that can be critical for nondigital natives), for instance (see "Bridging the gap between the finance team you have—and the one you need," CFO Insights, January 2019).

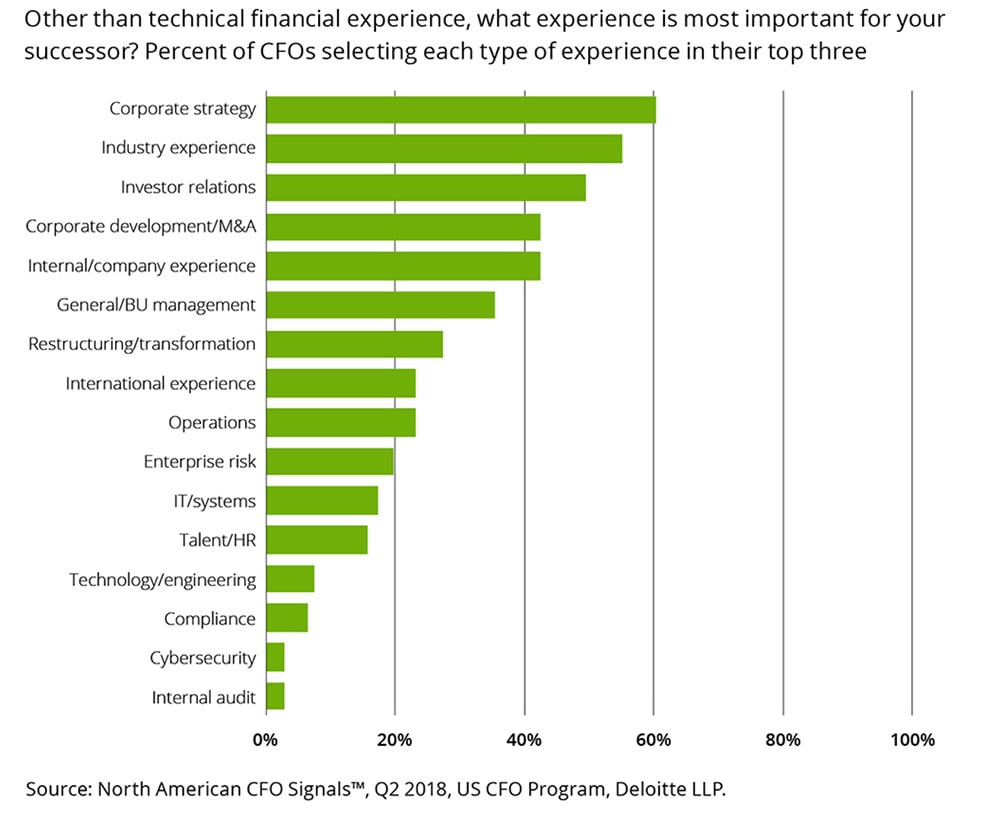

Whatever the approach, the goal is to broaden the perspective and experience of these potential leaders and prepare them to deal with a future that will differ, possibly drastically, from today (see Figure 2). For CFOs and finance professionals, that future may also mean roles outside of finance as their general business skills become even more valued. There are many examples of former CFOs who have been successfully promoted to become CEO or other general management roles. - Create short-term goals to sustain a long-term focus

One strategy organizations can borrow from behavioral science is to pursue longer-term outcomes by setting shorter-term goals. For example, instead of asking someone to plan for an event five years from now, organizations can break the task down into smaller, shorter-term components and ask people to complete one component in the next three months. Seeing leadership succession planning as part of their day-to-day job helps keep leaders engaged in the shorter term, while also proactively pursuing long-term success. - Establish tools, processes, and messaging to cultivate transparency and trust

Finally, distrust in the system can lead to disengagement and even unacceptable workplace behaviors. Organizations that use simple, accessible, and transparent data collection processes for succession planning and clearly communicate succession decisions using this data are often more successful. As with many other business processes, many leading companies are taking a design-thinking approach to succession planning, creating an experience that blends objective, disciplined methods with the intrinsic needs of the people for whom the process is designed.

Figure 2. Key experience for CFOs’ successors

Balancing empathy, objectivity, and discipline

The “holy grail” of effective succession planning turns out to be surprisingly obvious, but unsurprisingly difficult: balance empathy and attention to human factors with objective decision-making and the organizational discipline to see the process through. The hard part is encouraging current leadership to think and act in ways that enable the organization to achieve this balance. But the organization that succeeds can make that balance not just an effective part of its growth strategy, but also a signature feature of its corporate culture.

Where succession planning falls short

The leaders we spoke to gave the following reasons why they weren’t seeing succession planning deliver the expected value:

It’s a long-term discipline in a short-term world. By its very nature, succession planning efforts take years to bear fruit, while leaders are typically rewarded based largely on short-term accomplishments. One executive told us that, in his many years on the board of a Fortune 100 technology company, the only times the board discussed CEO succession were when a transition was imminent.

Succession planning can be destabilizing and threatening. Too often, succession planning is minimized because organizations don’t want the process to be perceived as a lack of confidence in their current executives. Similarly, executives are hesitant to raise the idea of succession planning lest it is perceived as them signaling their future intentions. This dynamic can have a destabilizing effect on an organization.

It’s unclear who is accountable for succession planning. Often, there is no clarity around whether the responsibility of planning for and grooming a successor sits with HR or with the business and/or functional leaders. Many of our surveyed leaders had no idea who was ultimately accountable for succession planning in their organizations. As one told us, “Even boards are often unclear on how CEO and executive succession accountability should be set—is it with one of the committees? The whole board? An individual? In many cases, there is no clarity for it and no one addresses it.”

Good data is either not available or ignored, leading to subjective decisions. Regardless of whether objective leadership data exists, many organizations can still default to subjective or political succession decisions based on factors such as likability, sponsorship, or tenure. We heard many examples of organizations investing in obtaining solid data (for example, through an executive assessment), only to have it thrown out and replaced by pure opinion. As one executive from a large health care company lamented, “Even with a lot of data, subjectivity and politics come into play.”

There is no clear process for succession planning. Many leaders said that their organizations lacked a strong methodology or tools around succession planning. One executive told us, “Boards and senior executives don’t know how plan for succession. If you ask them about financial oversight or executive compensation, they’re clear on how it works. But ask them about succession planning, and you get blank stares.”

Endnotes

1 Adam Canwell et al., “Leaders at all levels: Close the gap between hype and readiness,” Deloitte University Press, March 7, 2014.

2 Jeff Rosenthal, Kris Routch, Kelly Monahan, Meghan Doherty, "The holy grail of effective leadership succession planning," Deloitte Insights, September 27, 2018. The author team designed a year-long mixed-methods research study to understand why so few organizational leaders effectively engage in leadership succession planning activities. The study began in the summer of 2017 and was completed in July 2018. We sent out a survey to a random sample of more than 200 leaders across industries to determine the barriers and enablers to their leadership succession planning activities. Our survey also included an assessment with how strong they believed their current leadership succession program was and what could be done differently to enhance its effectiveness. After analyzing the survey data, we then sat down with over a dozen CEOs, board members, and HR leaders to conduct semi-structured interviews to further investigate the effectiveness of their leadership succession activities. We then used qualitative text analyses for the

interview transcripts to identify themes and patterns in the responses.

3 Brenna Sniderman, Kelly Monahan, Tiffany McDowell, and Gwyn Blanton, "Fewer sleepless nights: How leaders can build a culture of responsibility in a digital age," Deloitte Insights, October 31, 2017.

Contact us

Jeff Rosenthal

Managing director

Deloitte Consulting LLP

Kris Routch

Specialist leader

Deloitte Consulting LLP

Meghan Doherty

Manager

Deloitte Consulting LLP

CFO Insights, a bi-weekly thought leadership series, provides an easily digestible and regular stream of perspectives on the challenges you are confronted with.

View the CFO Insights library.

About Deloitte's CFO Program

The CFO Program brings together a multidisciplinary team of Deloitte leaders and subject matter specialists to help CFOs stay ahead in the face of growing challenges and demands. The Program harnesses our organization’s broad capabilities to deliver forward thinking and fresh insights for every stage of a CFO’s career—helping CFOs manage the complexities of their roles, tackle their company’s most compelling challenges, and adapt to strategic shifts in the market.

Learn more about Deloitte’s CFO Program.

Deloitte CFO Insights are developed with the guidance of Dr. Ajit Kambil, global research director, CFO Program, Deloitte LLP; and Lori Calabro, senior manager, CFO Education & Events, Deloitte LLP. Special thanks for Josh Hyatt, manager/journalist CFO Program, Deloitte LLP, for his contributions to this edition.

For more information on the financial reporting implications of disasters read this edition of the Financial Reporting Alert, which covers asset impairments; income statement classification of losses; insurance issues; environmental remediation, liabilities, clean-up and operating losses; stock compensation performance conditions and modifications; derivative and hedging considerations; employee benefits issues; assistance received from outside entities (e.g., Red Cross), disclosures; regulatory relief issues as well as other considerations.

Recommendations

Unleashing blockchain in finance

CFO insights