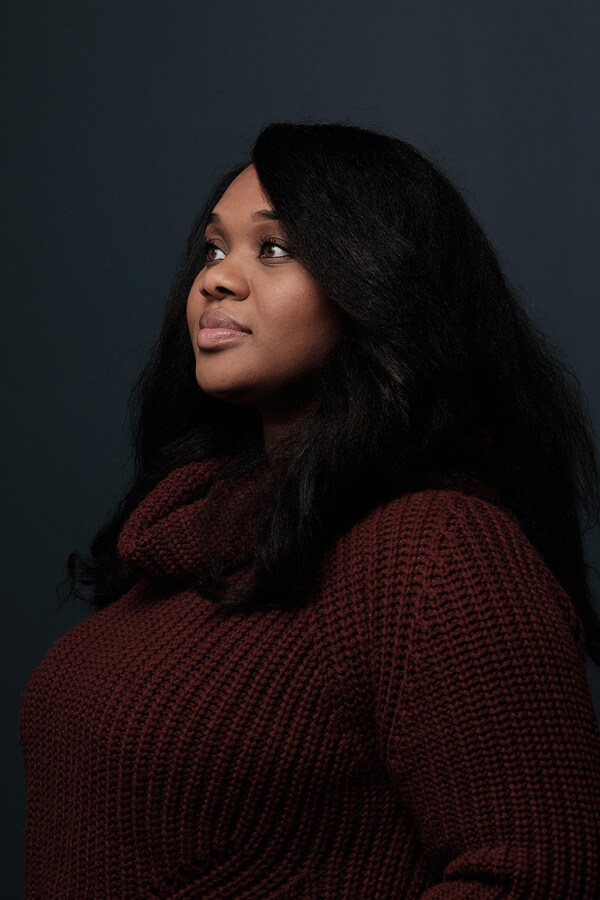

Nkiruka's Story

In August of 2014 while traveling on client business, I met a coworker in our hotel lobby to celebrate my birthday. She asked how I was doing. I said, “Everything’s crazy ... have you seen what happened with Mike Brown?” She shrugged her shoulders and seemed genuinely perplexed. I asked her to turn around to see the large television screen in our hotel lobby projecting the nonstop news reel of Mike Brown’s lifeless body on the streets of Ferguson, Missouri.

Six years later, we’re still seeing similar tragedies on our streets and in the news. So, what’s different about this specific moment in time? COVID-19 has made us focus.

The pandemic hasn’t just forced us to stay indoors. It’s forced us to pay attention to the news and the public health crises affecting our country—because our very health and livelihoods depend on understanding what’s going on. We’ve all had a lot of time to think about this terrible situation that often feels like it's not getting better. It’s during this very period that we saw the killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020. Everyone was watching. Everyone was paying attention. And everyone saw—and understood—that things had to change.

Regardless of race, I think people need to start recognizing that the United States doesn’t educate us to be racially aware—and definitely not to become change agents for racial equity. If you’re not a person of color, you likely don’t have the lived experiences to learn about systemic issues informally through culture. Many Americans live a life completely removed from the experiences of Black Americans—even when they happen to be neighbors, roommates, colleagues, friends, and companions.

Growing up in the small, rural, and segregated town of Ville Platte, Louisiana, I learned at a young age that although there was an inherent value to hard work, the contributions of the local Black community were often discounted. In my town, there were so many ways to arrange work that reinforced systemic inequities that were already in place. Many of the men in my family worked as day laborers from dawn till dusk for less than $3 an hour. Even before I was legally allowed to work, I can recall helping the women in my family earn income that we all depended on, even though their wages were not guaranteed or protected. I helped my grandmother clean houses. I sold “co-cups” for our neighbor. I made pies to sell at church on Sundays.

When I was 10, our family moved to Phoenix, Arizona, and by the age of 14, I got my first full-time summer job selling magazine subscriptions as a telemarketer. I found the environment was toxic, unprofessional, and sexist. I focused intently on what I could take away from the experience. I learned how to make a connection with potential customers in seconds; I learned to develop clear messaging on subscription features and benefits; and I learned how to tell a story to sell an experience, rather than a product. I wasn’t selling magazine subscriptions, I was helping an 80-year old woman get uninterrupted access to her favorite recipes, health tips, and inspirational stories—without ever having to leave her home.

It was during a subsequent job at a credit card customer service center—before adequate laws had been established to protect consumers—that I first gained my conscious awareness of social injustice perpetuated by workplace policies and processes. Just think about why many people call. They’re either going to be late on a payment or they’re being charged ridiculous fees. It didn’t seem at all fair on so many levels. There were all these little traps being set for customers rather than exploring positive ways to engage them. I couldn’t get my head around charging our own customers a $25 fee when they’d gone over their credit limit by just 20 cents.

That’s when I really started to become aware of—and question—how businesses operated, as well as the ethics behind their policies and processes in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society. Eventually, I chose an educational and career path at the intersection of leadership, organizational change, and workforce development.

Since many of our family members from Ville Platte sacrificed finishing high school in order to work as day laborers, the matriarchs—my great-aunt, aunt, and mom—made learning non-negotiable for those of us who could. This environment made learning like a second skin for me. Since working at Deloitte, I’ve worked and studied full-time, always wanting to use my knowledge to help others thrive in the workplace. I didn’t always know that I wanted to use learning, leadership, and workforce strategy as a platform for my career, but I wholeheartedly believe that my family’s emphasis on learning, education, and development was necessary for my own personal growth.

I’m currently doing my doctoral research on systemic bias in organizations and approach most situations at work both as an employee and a researcher. I spend all day thinking about the human experience and can honestly say I’ve had a largely positive experience working at the firm. Deloitte has been invaluable to my growth and development. If you were to enumerate all the support, mentorship, and exposure opportunities someone should receive during their career to be successful, I’ve gotten all of that and more.

We must have conversations where we give someone the gift of candor and make them aware of the moments when we felt invisible.

While I am incredibly grateful, I want to be honest. There have also been moments that really challenged me. I’ve had to think about why I stay at the firm and what needed to change for me and others to continue to grow and prosper. I’ve also thought about how the world is changing and whether or not the firm’s pace of action around social impact issues concerning racial and gender equity, immigration, and sustainability will suffice.

Over the past six months, Deloitte has begun to realize that we wield an incredible amount of power, influence, and resources that could be used to set an example of how organizations—and our communities—can increase racial equity and have a positive impact on human lives.

But we are on a journey, and sometimes the points on that journey won’t be reflective of where I personally want Deloitte to be heading. For example, a few years ago, the firm broadened its view of diversity to include diversity of thought. I felt like the firm was positioning diversity of thought as an alternative to traditional diversity, rather than seeing how the diversity in our thinking may be partially informed by our diverse social experiences which strongly correlate with traditional notions of diversity. And until more recently, I felt like it was taboo to even say the words “race” or “Black” in this firm.

That’s when I realized that my experience as a Black woman in this country—and my understanding as a scholar around this issue—would sometimes create divides between me and this firm that I love so much.

I haven’t always confronted those situations that created a divide. But I think it’s important to address them so people can be more aware of—and understand the implications of—their words and actions.

Another example occurred a few years ago, when I attended a women in leadership conference in which the presenter opened with a comment that included “even Black men had the right to vote before women.”

Sit with that for a minute. Because I know I did.

To me, this meeting was kicked off with my two identities being put in opposition to one another. Not only was I frustrated with the comment, but I became viscerally aware of how invisible Black women are in gendered spaces. I was amazed how the presenter was able to compartmentalize race and gender. She acknowledged women as a whole, but then treated Black men as their own unique racialized and gendered entity. It was like magic—something I could never do as a Black woman.

So, while making eye contact with the only other Black female manager in the room, I thought: Were Black women not included when she talked about women?

I decided, in that moment, not to address the speaker’s opening remarks. In the long term, the incident caused me to step away from participating in any other women’s initiatives at the firm that did not step into conversations on race. If that situation took place today, I would definitely say something. We must have conversations where we give someone the gift of candor and make them aware of the moments when we felt invisible.

Despite some missteps, I believe that leaders at Deloitte genuinely care about our people and the world’s potential for change. We are committed learners and have a profound respect for the personal histories and narratives of the individuals on our teams. Although our appreciation for storytelling is an invaluable uniting force in our culture, that is very different than recognizing and reconciling the very real power and privilege that comes with our position in society and what we can accomplish with the resources at our disposal.

I don’t think Deloitte has gotten it right yet. As an organization, we still have a lot that needs to be unpacked, unlearned, and redesigned. But at least the journey has begun.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely Nkiruka's own and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of Deloitte or its personnel.

Photos by Kirth Bobb